A Massive Meteor Hit Earth Last Year; Almost No One Noticed

A massive meteor explosion over the Bering Sea three months ago went completely unnoticed until just now, when scientists reviewed low-frequency acoustic wave data picked up by global recording stations. The 32-foot diameter meteor exploded on Dec. 18, releasing 173 kilotons of energy – about 10 times that of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

This latest meteor explosion was the second largest impact in the past 30 years, coming in behind the Chelyabinsk meteor of 2013 which caused a number of injuries and was widely captured on video.

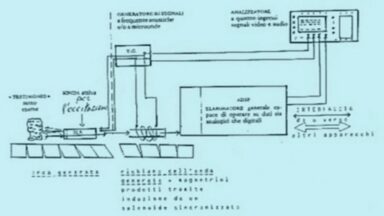

But unlike Chelyabinsk, this recent explosion took three months to be detected by a scientist studying infrasound data, which is inaudible to humans, but recorded by 16 monitoring stations around the world. The explosion is even being compared to the Tunguska event of 1908, during which a meteorite leveled an area of Siberia that included somewhere in the range of 80 million trees.

The explosion occurred in an incredibly remote area of the planet over an ocean where, luckily, no air traffic was passing through at that moment. But the fact that meteors this size with devastating potential, can enter the atmosphere almost undetected is a little unsettling.

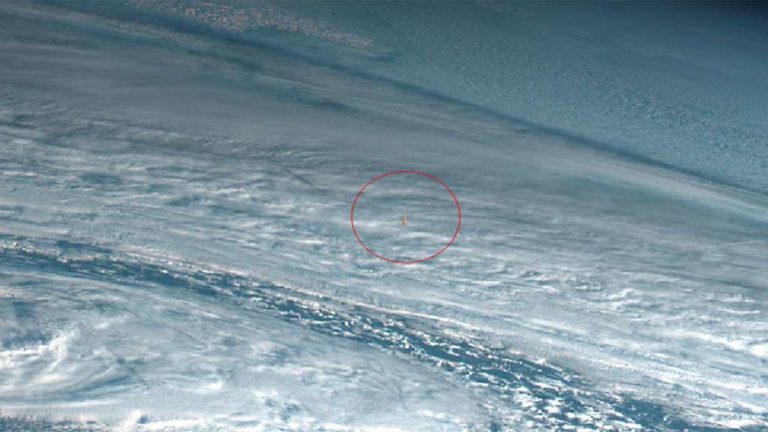

While it wasn’t witnessed or officially recognized until now, footage from a Japanese weather satellite happened to capture an image of the explosion as it entered the atmosphere between Russia and Alaska.

The meteor explosion caught by the Japanese Himawari-8 satellite Simon Proud, University of Oxford/Japan Meteorological Agency

Scientists often refer to a meteorite this size as a city-buster due to its potential to level an entire city, and bolides this size tend to enter our atmosphere a few times per century.

Reassuringly, most of the larger asteroids floating in our general vicinity have been mapped out and are regularly monitored by scientists at various observatories – even if we don’t necessarily have the means to deflect them if they were on a crash course with Earth.

But these mid-size rocks are particularly troubling, especially as man-made space debris can lead to collisions and changes in trajectory.

The technology and cataloging of 90 percent of all near-Earth asteroids larger than 450 feet in diameter is underway, but may take several decades. But these are only the rare nation-busters that would wipe out an entire country; mapping out all of the smaller city-busters is something that hasn’t really been considered, if it’s even possible.

Seems like it might be time someone builds a machine learning algorithm to do that for us.

For more on near-miss asteroids check out this episode of Beyond Belief with Dan Durda:

Decades After Landing on Mars, We May Find Proof of Past Life

After 25 years of rovers landing on Mars, many are looking forward to the next chapter of Mars exploration, which may include excavating deep into the red planet. In July 1997, NASA’s Pathfinder landed on Mars and began its mission to demonstrate how a robotic rover would land on the red planet.

Using an innovative design, the rover landed on Mars with a parachute and a series of giant airbags to cushion its blow. The Carl Sagan memorial station and the Sojourner Rover outlived their projected lifespan, and in the years following sent magnificent images back to Earth.

The lander returned more than 16,500 images and the rover sent back 550 more, in addition to chemical analyses of rocks, soil, and data on wind and weather. The final transmission from the Mars Pathfinder was on September 27, 1997, but the data it provided helped scientists to conclude Mars was once wet and warm, and rounded rocks on the surface indicate they may have been worn down by running water, and if there was water, there could have been life.

Flash forward to today, NASA’s Perseverance Rover, on the red planet since February of 2021, is tasked with finding past or present life and seeing if humans could one day explore or colonize Mars.