Ancient Mistletoe Could Be the Next Alternative Cancer Treatment

Mistletoe, an ancient parasite plant that grows on several species of trees, has been harvested for centuries. Loaded with symbolic traditional meaning, 21st century scientists at the Johns Hopkins Cancer Research Center are studying Viscum album, its latin name, to understand why mistletoe appears to relieve cancer symptoms and fight tumors. But a look back to the recorded history of mistletoe casts a light on the significance of the plants to humanity, at least as far back as the first century A.D.

Mistletoe History — the Druids

On the sixth day after a new moon, a group of Celtic druids, accompanied by two magnificant white bulls, gather around an ancient oak — a “king tree.” The leafless limbs of the venerable tree are festooned with shaggy green spheres dotted with white berries.

This auspicious day, when mistletoe appears on the sacred oak, is being marked with solemn ceremony — the Ritual of Oak and Mistletoe. This special mistletoe is harvested and hoarded to bless newlyweds, mark new alliances after wars, make medicines, and bring special luck in times of need.

Mistletoe, common to the forests of Gaul and Britain, is gathered for medicines and luck, but the appearance of mistletoe on oak, the chieftain of the trees, only happens a few times over many generations, if that. To harvest the sacred plant, priests climb into the branches carrying blessed blades to sever the greenery from the honored limbs. Others circle the trunk holding linen cloths to keep falling mistletoe boughs from touching the ground. After, to give thanks, the druids sacrifice the white bulls.

The Myth of the Death of Baldur

Scratch a Swede or a Dane and they’ll bleed pagan Norse myths. Scandinavia was the last part of Europe to convert to Christianity — a life-or-death ultimatum from Charlemagne did the trick. But the Norse pantheon and mythology persists in the Viking collective consciousness — the story of the death of Baldur is no exception, and mistletoe plays a featured role.

In Valhalla, home of the gods, Baldur, son of Odin and the good sorceress Frigg, was the most beloved of all. When Baldur began to have alarming dreams of misfortune, Odin disguised himself and travelled to the underworld to consult with a dead seeress who specialized in dreams. When he arrived, the underworld was in a whirlwind of preparations for a feast.

Odin, disguised as a wanderer, woke the seeress witch and asked who would the celebration would honor — she explained that the festivities were in preparation for the arrival of Baldur. She explained how Odin’s beloved son would meet his end, but when the wanderer became distressed, she realized she was talking with Baldur’s father Odin.

The chief of the gods didn’t waste time getting back to Valhalla to tell Frigg, who, upon hearing Odin’s tale, travelled the entire length and breadth of the cosmos to extract an oath from every being and thing; to never harm her son Baldur.

After, rocks and sticks simply bounced off Baldur, as they had all sworn they would never hurt him. But Loki the trickster donned a disguise and approached Frigg with the question, “Did you really get ALL beings to promise never to harm Baldur?”

Frigg replied, “Yes — everything but the innocent mistletoe. How could such a small, gentle thing hurt my son?”

Loki hustled away and made a mistletoe spear. The short story is that he got the blind god Hodr to throw it at Baldur, killing the shining son of Odin. The ensuing pandemonium in Valhalla, the underworld, and on earth, is long and complicated, but importantly, Frigg’s tears of grief fell on the mistletoe and turned into white berries. For some reason she blessed the plant and promised to kiss anyone passing beneath it. Thus our tradition of kissing under the mistletoe.

Healing Mistletoe Traditions

Pliny the Elder (23 to 79 A.D.), a Roman “natural philosopher,” recommended mistletoe for epilepsy and tumors, as did Hippocrates, called the “father of modern medicine.” The Celts used mistletoe juice on external cancers, and the name, meaning “all heal” is thought to be derived from the Celtic language.

The plant has been used in traditional Chinese medicine, and Rudolf Steiner, founder of “anthroposophical medicine” suggested that mistletoe could be a treatment for cancer. Steiner may be responsible for sparking scientific interested in the plant.

Modern Mistletoe Cancer Research

According to an article published by the National Cancer Institute, “Mistletoe products vary, depending on the type of host tree on which the mistletoe grows and the time of year the plant is picked.” The article cites studies on mistletoe and cancer; one 2000 study concluded that, “Patients treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy and given mistletoe [during treatment] had fewer adverse events, better symptom relief, and improved disease-free survival compared to patients who did not receive the [mistletoe] therapy.

A 2013 study found that 220 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with mistletoe had improved survival rates and fewer symptoms common to pancreatic cancer — fatigue, nausea, weight loss and diarrhea, compared to those not given mistletoe. A study done on non-operable lung cancer completed in 1987 reported that patients receiving mistletoe had an improved sense of wellbeing “compared to patients in other groups.” In addition, 22 research trials concluded that cancer patients had improved quality of life with mistletoe.

Johns Hopkins Magazine

In the Spring, 2014 issue of Johns Hopkins Magazine, journalist Joe Sugarman wrote about a 37-year old woman, Ivelisse Page, who developed liver cancer p0st-treatment for colon cancer. Her Johns Hopkins oncologist, Luis Diaz M.D., told Page she had an eight percent chance of surviving more than two years. Page underwent surgery to remove one-fifth of her liver, but after, chose a treatment path less travelled.

Page consulted with Baltimore doctor Peter Hinderberger M.D., a specialist in complementary and alternative cancer therapies. He had seen “positive effects from injections of mistletoe extract,” and suggested she try it in lieu of chemotherapy. Traditional oncologist Diaz wasn’t enthusiastic, but reviewed European mistletoe studies; he ultimately agreed that Page could try mistletoe therapy instead of chemo.

At Page’s next visit to Diaz’s office, he was, “Amazed — I noticed that as soon as she went on the mistletoe she started feeling better.” He went on to say that her color improved and she had more energy. Ultimately, post-surgery, Page had been cancer-free as of the time the article was published in 2014.

Additional Research

Although not yet approved for treatment, mistletoe continues to be a focus for research . Currently The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine is conducting clinical trials on mistletoe as a cancer treatment.

A 2016 study published in the “Journal of Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine” concluded that, “Integrative cancer treatment including MT [mistletoe] aims to help patients live well with their disease. Intravenous MT may particularly support patients in advanced stages and help improve quality of life…and help to positively affect a patient’s tumor situation.”

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to diagnose or treat disease. The information on this website is not intended as a substitute for the consultation, diagnosis, and/or medical treatment of a qualified physician or healthcare provider.

Simple Tapping Technique Found to Lower Stress, Boost Immunity

In the latest research on emerging energy healing techniques, one modality is quickly proving itself to be unusually effective in bringing about immediate psychological relief and is done with just the tap of a finger.

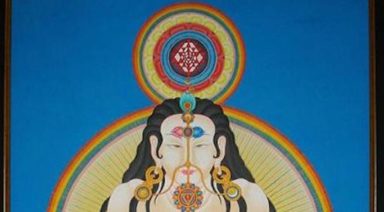

Emotional Freedom Techniques — or EFT — are a powerful self-healing practice that seeks to address psychological issues by working with energy channels in the body. Also known as tapping, it combines modern psychological therapies with ancient healing technology.

Specifically, EFT incorporates the principles of acupressure, which involves the application of pressure to specific points in the body — thought for thousands of years to clear blockages along energy channels or meridians.

Dr. Dawson Church is a health and science writer who has been researching, practicing, and teaching EFT for decades.

“EFT’s history goes back thousands of years. Researchers have discovered mummies from Europe that are over 5,000 years old with these tapping points tattooed on their bodies. And acupressure is simply pressure on acupuncture points like we would normally use needling on them. Instead, we use pressure or fingertip tapping on those points.,” Dr. Church said.

“What we do with EFT is we simply organize several of the most potent points of acupuncture into a little ritual so you can remember to tap. The research shows that if you take somebody who’s stressed, the emotional brain — the central part of the brain, the limbic system — is highly active. When you have them tap while remembering a painful incident, it simply calms the brain down in a few seconds.”