Archeologists Uncover 200 New Stones, 15 Temples At Göbekli Tepe

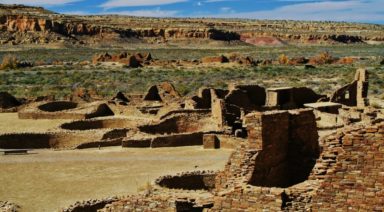

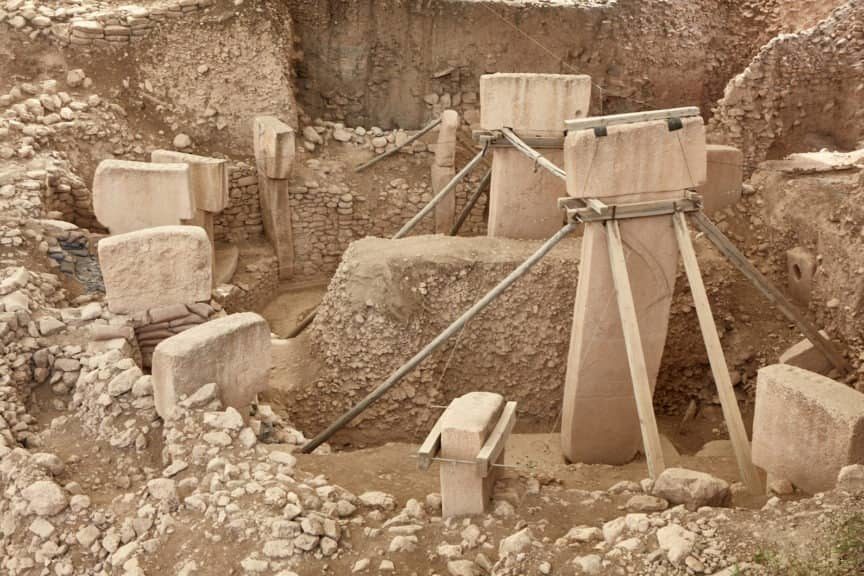

Archeologists recently discovered at least 15 new megalithic temples and over 200 standing stones at Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, the oldest archeological site in the world. The excavations predate what was originally thought to be the oldest evidence of human settlement, Çatal Höyük, and are so extensive they will likely require another 150 years of excavation.

The site was reopened partially in February, after being closed to visitors so archeologists could work on its restoration. UNESCO recently added Göbekli Tepe to its list of world heritage sites, with the majority of the complex remaining underground.

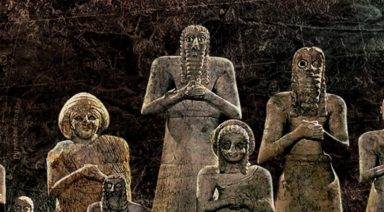

Göbeklie Tepe, meaning “potbelly hill,” has baffled archeologists for years, after it was dated to have been built before modern agriculture or the discovery of metal, despite the multitude of carved obelisks used in its construction. These massive stones are T-shaped, weighing between 40 to 60 tons, and standing between 10 to 20 feet tall.

According to mainstream archeology, the site served no practical purpose because it appears that it was not used for housing, and was allegedly built by hunter-gatherers. It was discovered by archeologist Klaus Schmidt, who excavated the site from 1996, until his sudden death in 2014.

But Göbekli Tepe is comprised of intricately carved stones as large as the rocks at Stonehenge, built 7,000 years later. The idea that a group of hunter-gatherers with primitive stone tools could construct a site of this magnitude is astonishing. Alternative theorists believe there may be more to the story.

Others believe the site could be evidence of a lost civilization that drastically predates mainstream archeology’s official timelines. Graham Hancock points out that the site contains the first perfectly north/south associated buildings, alignments to specific star groups and specific moments of the year, meaning this culture had a strong grasp on astronomy.

Boston University Professor Doctor Robert Schoch, posited the idea that an ancient, advanced culture predating traditional civilizations may have existed before the end of the last ice age, before it was wiped out in a cataclysmic event around 9,700 BCE.

Schoch says he believes that a solar induced dark age occurred after a massive solar flare took place, forcing existing civilizations to retreat underground, or as is the case with Göbekli Tepe, to bury their structures for preservation. He believes this culture eventually died out, as human populations descended back into a stone age, until the cycle of civilization sprung up again in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.

Schoch points to the Sphinx and the water erosion hypothesis as potentially having a connection to this culture. Schoch and other proponents of alternative archeological timelines believe the Sphinx predates ancient Egyptian civilization, due to water erosion on the side of the sphinx; the annual average rainfall that would have been enough to cause this type of erosion ended thousands of years before the Sphinx was allegedly built.

As Graham Hancock likes to say, “stuff just keeps on getting older.”

Learn more about Göbekli Tepe from the research of Andrew Collins in this episode of Beyond Belief:

An Ancient Psychedelic Brew & Metal Found in an Elongated Skull

Did ancient Peruvian leaders use hallucinogens to keep their followers in line? And do an ancient elongated skull show evidence of an advanced metal surgical implant or is it just a hoax?

Archaeologists studying the Wari people in the southern Peruvian town of Quilcapampa have found hallucinogenic “vilca” seeds in a recent dig. Writing in the journal Antiquity, the researchers point out they found 16 vilca seeds in an ancient alcoholic drink called “Chicha de Molle,” in an area believed to be used for feasting.

The Wari people lived in this area from about 500 to 1,000 A.D. Their reverence for the psychotropic vilca seed has been found in images at other Wari sites, this is the first find of the actual seeds. What is particularly interesting to the archaeologists is the role of ancient hallucinogens and their influence on social interactions.

The vilca seeds would have come from tropical woodlands on the eastern side of the Andes, a complex trade network would have to be in place to even get them. And adding the vilca seeds with the alcoholic drink would increase the intensity of a psychedelic trip.

That trip would be seen as a journey to the spirit world, and Wari leaderships’ control over the substance led to control over their followers who wanted it. Researchers argue in their paper, “[T]he vilca-infused brew brought people together in a shared psychotropic experience while ensuring the privileged position of Wari leaders within the social hierarchy as the providers of the hallucinogen.”

Work continues at the dig site at Quilcapampa, and researchers plan to test where the ancient vilca seeds came from – so they can figure out the rest of the ancient trade routes.