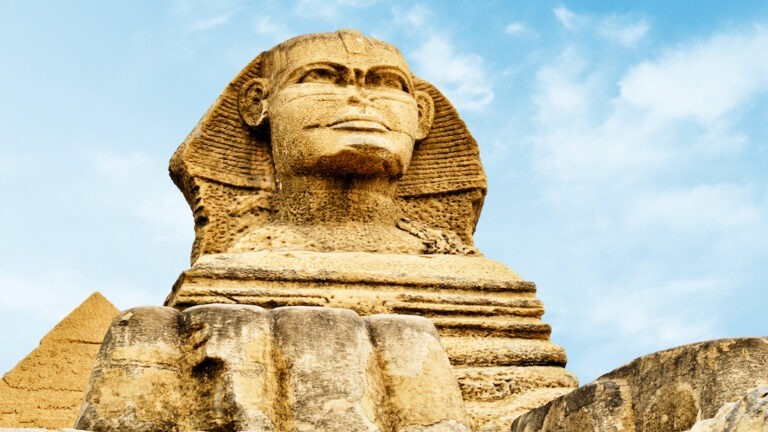

Decoding the Actual Age of the Great Sphinx

Posing as a sentinel on the Giza plateau is the weathered and colossal figure that stands 66 feet above the desert sand, the Great Sphinx, a limestone sculpture with the head of a lion and the body of a human. While we now know much about the history and mythology of the ancient Egyptians, the mystery of the Sphinx has yet to be truly unraveled.

An ongoing battle between mainstream Egyptologists and a more recent wave of independent thinkers debates the age of the Sphinx by thousands of years. The latter insists the imposing limestone statue is much older than mainstream archaeologists, and Egyptologists claim it to be.

Mainstream archaeologists determined the Sphinx to have been built between 2558 and 2532 BCE. But in 1992, John Anthony West rocked the scientific community with his claim that the Sphinx was actually carved 10,000 years earlier before Egypt was a desert. West and others argued that academia had overlooked an important detail—the body of the sculpture bore distinct markings of water erosion.

After his assessment of the Sphinx’s age, West found fellow scientists who shared his observation about uncovering an entirely different history than was commonly accepted. West’s search led him to Robert Schoch, a geology professor at Boston University, willing to pursue an open-minded, out-of-the-box investigation into the origins not only of the Sphinx but the entire region, as well as its implications for the origin of the human species.

In Gaia’s original series, Ancient Civilizations, Schoch explains his first encounter with the figure in 1990, at which time he immediately noticed there was a disconnect between the statue’s academically accepted date of origin and the truth staring him in the face. Upon careful inspection, Schoch realized the Sphinx survived intensely wet weather conditions that stand in stark contrast to the now hyper-arid conditions of the Sahara Desert.

Schoch concluded that academia had determined the Sphinx’s age by overlooking signs of erosion due to heavy rainfall. The deluge that eroded the Sphinx was uncommon to the Egyptian plateau 5,000 years ago, but very common 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. For Schoch, this was an exciting find, but for mainstream science, it was met with derision and denial.

How Old is the Sphinx Really?

According to the research of Manichev and Parkhomenko, “large bodies of water” partially flooded the Sphinx monument creating “wave cut-out hollows on its vertical walls.” One erosion mark, in particular, appears in a large hollow of the Sphinx and corresponds to the water level of the early Pleistocene Age. From such evidence, geologists concluded that the statue was already standing on the Giza Plateau by that time.

Astoundingly, they also made the claim the Sphinx could be up to 800,000 years old, when the Mediterranean Sea extended all the way south into Egypt and onto the Giza Plateau. This would explain the statue’s distinct marks of erosion — caused by seawater lapping up against it over thousands of years.

But Andrew Collins suggests that, while this rock formation may have been kissed by the Mediterranean Sea, the actual statue may have been carved out of it at a much later date. In short, the rock is ancient, but the statue is relatively less so.

In 1991, Professor Schoch scientifically dated the Sphinx to thousands of years prior to the time of the Egyptian pharaohs, having been constructed at the end of the last ice age. This places the statue at a time when the Saharan region was much more humid, lush with plant and animal life, and subject to persistent rainfall. And despite constant criticism from mainstream archeologists, he’s held his ground, showing seismic data of the region which suggests the Sphinx’s origin may be more accurately placed at 10,000 B.C.E.

The Debate Heats Up

Researcher Graham Hancock also weighs in on the Sphinx’s age noting the statue appears to have been exposed to about a thousand years of heavy rainfall. Because there was no rainfall in that area during the time of the pharaohs, or for thousands of years prior, Hancock says he believes the Sphinx needs to be placed more than 12,500 years back.

Egyptian-born writer and engineer Robert Bauval famously argued that there are no inscriptions on the Sphinx “either carved on a wall or a stela or written on the throngs of papyri that associates” the statue with the time period of the pharaohs of ancient Egypt as we know them.

As it has throughout its history, the Sphinx continues to be restored from constant erosion and remains an alluring and enigmatic landmark of the ancient past. But it seems clear that mainstream Egyptologists remain stalwarts in refusing to reevaluate these artifacts of antiquity, as doing so could mean changing the narrative and minds of academia worldwide.

Japan's Yonaguni Ruins May Hold the Key to a Sunken Civilization

The mystery of the lost continent of Atlantis has puzzled researchers for centuries, as growing evidence supports the theory that an advanced civilization may have been destroyed and gone unnoticed by mainstream archeology. This antediluvian civilization is assumed to have been located somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean and is thought to have been the progenitor of ancient civilizations like those in Egypt and India. But could there have been another sunken continent from that era that predates Atlantis? The Yonaguni ruins might provide an answer.

The Yonaguni Monument

In 1985, a Japanese diver named Kihachiro Aratake was exploring the seafloor off the Southern shore of Yonaguni-Jima island, the Western-most island in the Ryukyu archipelago of Japan. Aratake came across what appeared to be the sunken ruins of an ancient, megalithic, stepped pyramid, similar to the ziggurats built in ancient Sumer. Since his discovery, the provenance of the ruins has been debated as to whether they are man-made or naturally occurring, due to the possibility of natural geological terracing.

Dr. Masaaki Kimura from the University of Ryukyu is the biggest proponent for the theory supporting the artificiality of the ruins. Surprisingly, Dr. Robert Schoch is one archeologist who has contended Kimura’s theory, despite his support for the Sphinx water erosion hypothesis. Although, Schoch has conceded that he doesn’t perceive Yonaguni to be a closed case and that he hasn’t spent as much time diving there, compared to Kimura’s 15 years.