Is a Tesseract a Wrinkle in Time?

Did a coming of age story set in a science fiction context plant the seeds of quantum physics in popular culture in the 1960s? When Madeleine L’Engle wrote “A Wrinkle in Time” in the late 1950s, quantum theory was in its infancy, but was being nurtured by the likes of Max Planck, Niels Bohr, and a cohort of other theoretical physicists.

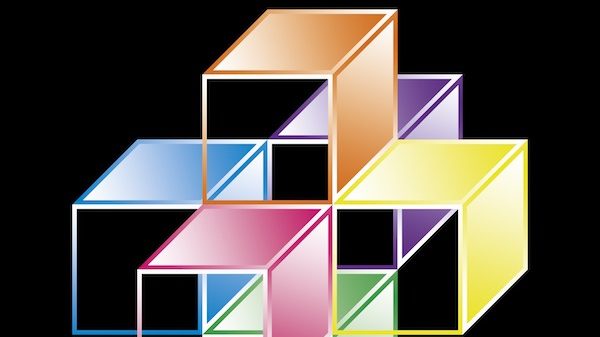

In 1962, L’Engle entered new literary realms with the adaptation of quantum physics in the form of the “tesseract,” a theory of dimensional travel. She also brought a female protagonist to the male-dominated science fiction genre, another groundbreaking move. That was 50-plus years ago — now the tesseract model, essentially a 4D analogue of a cube, appears in fiction, comic books and film, and is used by science to describe dimensional processes and systems such as DNA sequences.

After being rejected by at least 40 publishers, L’Engle’s book “A Wrinkle in Time,” was finally published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and went on to win the prestigious John Newbery medal in 1963. The book, an instant classic, continued to garner honors over the following five decades. Fourteen million copies of “A Wrinkle in Time” have sold since the first edition.

The word “tesseract” was invented by eccentric British mathematician and science fiction writer Charles Howard Hinton, who coined the term in his 1888 article, “What is the Fourth Dimension.” Quantum theory is now common parlance in theoretical physics. But L’Engle’s prescient story-telling introduced tesseract theory to generations of young readers. This notion of interdimensional travel via the tesseract was seeded into collective consciousness and continually appeared above the pop culture waterline in the form of comic books and film.

“Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space.” Dr. Amelia Brand, “Interstellar”

In 2006, “Tesseract the Everywhere Man” appeared as a character in a 2006 comic book series, the Ultimate Fantastic Four #33. Tesseract as a thing rather than a theory appeared as “The Cosmic Cube” in Marvel Comics in 1974 — a talisman giving cosmic powers to the possessor, with several iterations throughout the franchise.

In film, A thriller starring Jonathan Rhys-Meyers, “The Tesseract,” was released in 2003, based on a book of the same name by Alex Garland. “Captain America: The First Avenger” was the next movie in 2011. The cinematic “cosmic cube” has been punted from one Marvel movie franchise to another, i.e., the “Thor” series and “The Avengers.”

In film, a thriller starring Jonathan Rhys-Meyers, “The Tesseract,” was released in 2003, based on a book of the same name by Alex Garland. “Captain America: The First Avenger” was the next movie in 2011. The cinematic “cosmic cube” has been punted from one Marvel movie franchise to another, i.e., the “Thor” series and “The Avengers.”

The tesseract returned to big screens in “Interstellar” in 2014 — a big-budget, science fiction movie starring Matthew McConaughey, Jessica Chastain, Anne Hathaway, and Michael Caine. And now the tesseract has returned home, travelling full circle with the March, 2018 release of “A Wrinkle in Time” based on L’Engle’s book.

In the book, the tesseract was described by a simple line drawing of an ant traveling on a string held taught. But in “Interstellar,” the tesseract is imagined as a complex, dimensional grid structure accessed via the event horizon of a black hole. This reflects the complexity of the theory, now fleshed out by geometry, describing the tesseract as a “four dimensional analog of a cube — the tesseract is to the cube as the cube is to the square.”

Beloved of physicists and mathematicians, tesseract theory, part of relativity theory, now encompasses formulas and descriptions of Euclidean space. Theorists use the tesseract concept to describe multi-dimensional space or objects. According to mathforum.org, “Physicists suggest that the extra dimensions are quite large; so large that our world exists inside of a higher-dimensional reality.”

Others posit that the tesseract is actually a model of the universe, while some use art to describe the concept. Economists and biologist have adopted the theory to visualize the state of systems in imaginary space. Life scientists use the model to describe DNA sequences as dimensional “hypercubes” to understand mutations in viruses.

In 2003, “A Wrinkle in Time” was adapted for a Disney-produced television movie premiering at the Toronto Children’s Film Festival, and as a Disney special in 2004. This version received negative reviews — even L’Engle said, “I have glimpsed it…I expected it to be bad and it was.”

But the story has at last returned as a feature-length film that stays true to the plot by putting the sophisticated concepts of tesseracts and multi-dimensionality under the dominance of a universal concept of love. While “Interstellar” explores these theme from a different angle, it arrives at a similar conclusion — that love and gravity are the same energy, and that powerful loving intention actually directs gravitational force. In “Interstellar,” Dr. Amelia Brand, played by Anne Hathaway, says, “Love isn’t something we invented. It’s observable. Powerful. It has to mean something. Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space.”

Swiss Physicist and researcher Nassim Haramein, in his work in physics, quantum mechanics, comes to a similar conclusion, asserting that “Love is the unified field of everything.”

Many observe the convergence of spirituality and science as a cultural revolution that redefines what have been, up until recently, two seperate paradigms. The controversial comedian Bill Hicks, who died in 1993, came to a similar conclusion. “It’s just a simple choice, right now, between fear and love. The eyes of love see all of us as one. Take all that money we spend on weapons and defenses each year and spend it feeding, clothing and educating the poor of the world, and we could explore space, together, both inner and outer, forever, and in peace.”

The Mystery of Torsion Fields

Russian scientist Nikolai Kozyrev was considered a prodigy. In 1925, at age 17, he published his first scientific paper, which focused on astrophysics and the atmosphere of the sun and other stars. It was met with great acclaim by other scientists.

At age 20, he graduated from the University of Leningrad with degrees in physics and mathematics. By age 28, he was a college professor and distinguished astronomer. To the science community at large, this promising young physicist disappeared for the next 11 years.

Nikolai Kozyrev: Russian Concentration Camps

While Korzyrev was enjoying a successful career as a professor and researcher, Josef Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union, was feeling threatened by scientists whom he perceived were independent thinkers. He was concerned they would see through his propaganda program. To prevent this, in 1936, he arrested them and sent them to concentration camps. Nikolai Kozyrev was among those imprisoned. There wasn’t much for him to do during the long 11 years he spent in the camps except to observe, meditate, and think.

During his imprisonment, Kozyrev was enthralled watching bacteria grow and noticed it grew in a perfect spiral. This led him to conclude that all life-forms likely draw off of an unseen spiraling source of energy. This energy is as important to maintenance and growth of life as are “eating, drinking, breathing, and photosynthesis.”

Kozyrev also concluded that this spiraling energy and growth is how time works, with the Earth orbiting in space by way of a “complex spiraling pattern.”

As the Earth rotates on its axis as it orbits the sun, it releases energy, or torsion waves, that propel it through space. The torsion waves travel at speeds faster than the speed of light. These torsion fields are actually “waves of time” which also cause ripples in gravity. Indeed, some scientists now believe that “electromagnetism, gravity and torsion waves are all members of the same family; they are just different forms of ether vibrations.”