Meetings with Remarkable Men: A Viewer’s Guide

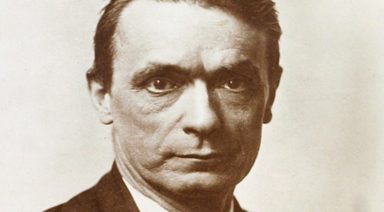

George Gurdjieff was an influential spiritual teacher, writer and musical composer of Armenian and Greek descent. Born somewhere between 1866 and 1877, he lived until 1949 and had many devoted followers. Gurdjieff developed a method called The Work and encouraged his students to rouse themselves from unconscious disembodiment (waking sleep) in order to reach their full potential as human beings and transcend to higher states of consciousness.

Awakening is possible only for those who seek it and want it, for those who are ready to struggle with themselves and work on themselves for a very long time and very persistently in order to attain it.

Gurdjieff

Gurdjieff’s “Fourth Way” teachings are said to unite the three incomplete, separate paths of spiritual awakening – physical effort, emotional processing, and mental endeavor – so human beings can evolve in a more balanced manner. Gurdjieff came to believe that it was no longer necessary for modern people to renounce the world and travel a traditional spiritual path in order to awaken. The Gurdjieff Method is meant to develop mind, body and emotions in an integrative manner, without the need for renunciation or limitations to creative freedom along the way.

Gurdjieff’s teachings thrive today through group meetings, the study of his ideas, playing and listening to music, the practice of Gurdjieff’s Movements and Sacred Dances, meditation and sitting, and other forms of artistic expression. Find out more through The Gurdjieff Foundation (USA), the Gurdjieff Society (UK), and Institut Gurdjieff (France) or through the Gurdjieff International Review.

Remarkable Men Reminder: Live In Awe and Question Everything

Who was Gurdjieff and what led him, as a young man, to leave his conventional life and go on an arduous journey of spiritual awakening? These are the questions director Peter Brook (Lord of the Flies, 1963) sets out to answer in his epic 1979 film, Meetings With Remarkable Men, based on the second book of Gurdjieff’s allegorical and autobiographical trilogy, All and Everything.

Why watch a movie from 1979? First off, Meetings With Remarkable Men is a cinematographic gem. It’s filmed in the mountains and deserts of Afghanistan, a place of stark, remote beauty. I probably read an article about the turmoil in Afghanistan every other day – but what do I really know about its landscape, people, climate, or cultural diversity? Not much. Director of photography Gilbert Taylor’s striking images will stay with you long after the final credits, and allow you to attach vivid pictures and deeper understanding to the next series of news stories coming out of Central Asia.

And the music! Laurence Rosenthal adapted Thomas de Hartmann’s compositions for the film. De Hartmann was an acclaimed Russian composer (and student of Gurdjieff) who co-wrote much of the music used in Gurdjieffian Movements and Sacred Dances. The score is at times both haunting and playful, and combined with the visuals, give the viewer a taste of what it’s like to be young and in awe, questioning everything – just trying to figure it all out in a confusing, often painful world.

Sound familiar? Yes, Kars in 1900, where Gurdjieff was raised, was a multi-ethnic crossroads, a melting pot of cultures, languages, and religions. With all the political and religious intolerance flaring up around the world today, it’s refreshing to see that people who looked, thought, acted, believed, and were raised very differently from one another could actually cohabitate – somewhat peaceably – in the middle of an unforgiving desert.

Viewer’s Guide: 15 Questions To Enhance Your Own Remarkable Men Journey

I knew very little about Gurdjieff or his teachings when I sat down to watch the film, but that didn’t matter in the least. All you need to bring is your curiosity and your willingness to travel through Central Asia, Iran, Egypt, the Gobi Desert, India, and the Himalayas with an earnest young man seeking answers to some of life’s most profound questions. It’s a journey we all need to take – and this one is both gorgeous and thought-provoking, well worth watching alone or in the company of family and friends.

The best way to watch the film is to hit the pause button along the way (in order to digest some of the more profound passages), rewind a bit (when an image strikes you), Google the places Gurdjieff travels (to get a deeper understanding of the breadth of his quest), and to discuss or contemplate particular scenes (especially those that resonate with your own spiritual journey).

Or better yet: Host a Screening Party for Meetings With Remarkable Men. Here are some questions that will help make watching the movie more provocative and relevant. So dim the lights and get comfortable – for 90 minutes you will be transported to another time and place, a place of wonder and awakening. Let’s go on a journey together!

- We’ll start by observing the opening scene. What is the symbolism of a teenage Gurdjieff (dressed all in white) walking with his father through a rocky desert landscape? When the music changes, Gurdjieff leaves his father’s side, scurries up a craggy hill, and sits alone on top, earnestly taking in the view. What is the boy looking for? What does he see? Can we be that wide open to earth, sky and spirit in our daily lives?

- Gurdjieff speaks with his father and their local Russian clergyman. “So your family wants you to become a priest,” says the priest. “Yes, but I am interested in science,” replies the boy. “Then study medicine, as well. Body and soul depend on one another.” Gurdjieff’s father counsels: “Become yourself. Then God and the Devil don’t matter.” Are these wise words? Is there truth to be found somewhere other than (or in between) science and religion? What’s the significance of Gurdjieff picking up the snake?

- What do you make of the cannon “challenge” and ensuing hospital scene? Notice the symbolism of a dark haired, dark-eyed Gurdjieff lovingly embracing the fair haired, light-eyed student. The injured boy asks: “Did you think you were going to die? Were you afraid? What did you feel?” Gurdjieff answers: “What’s it like, not to be here anymore?” What was the question or questions that started you on your own spiritual journey?

- Gurdjieff sees a Yazidis child “trapped” in a chalk-drawn circle – the child is distraught, but can’t seem to get out. Gurdjieff erases a piece of the circle with his foot, and the boy runs away. What does this mean?

- The movie jumps to Gurdjieff as a young man working in a factory in a large town. A friend, Sebastian, studying to become a priest, comes to visit from Kars. Gurdjieff jokes, “My father says, ‘If you want to lose your faith, make friends with a priest.’” When his friend admits to having questions about his chosen vocation, Gurdjieff replies: “Nothing convinces me either. Science proves one thing, religion another, and both seem equally true. I’ve read every sort of book – new, old. I’ve seen marvels which I can’t explain, and I am more thirsty than ever.” “What are you looking for?” asks Sebastian. “I want to know why I am here,” Gurdjieff answers. Discuss this passage. How does it relate to spirituality and personal growth? Is their line of questioning relevant today?

- The Road Movie begins! Gurdjieff says “There is a group of us here. Nothing will stop us until we find an answer…We must go… I’ll ride on the Devil’s back if necessary, as long as I get there.” What are these young people looking for? Is sacrifice necessary in order to find answers to life’s most profound questions?

- Gurdjieff explains to the Prince: “Ever since I was a child, I had the feeling that there something is missing in me. I felt that apart from my ordinary life. There is another life, a life which is calling me. But how to be open to it? This question never gives me any peace, and I have become like a hungry dog, chasing everywhere for an answer…I want to learn. I want to understand.” The Prince answers: “Be careful. What you call learning, if it means storing up experiences and beliefs, it will tie you like a cord and prevent you from knowing. Knowing happens directly when not even a thought stands between you and the thing you know. Then you see yourself as you are, not as you would like to be. I have learned how difficult this could be.” What is “knowing”? Are you like a “hungry dog” seeking answers? How can you prevent beliefs from “tying you like a cord” and preventing you from self-knowledge and true awakening?

- The Prince speaks with a “father” and has some tea. He laments: “I have seen many miracles and tried to explain them, but it has brought me no real understanding.” The father counsels: “If you feel with all your being that you are truly empty, then I advise you to try once more… I advise you to die, consciously, of the life you have lead up until now and go where I shall indicate.” When we chose to follow a spiritual path, do we have to relinquish control in order to progress more fully? What is the nature of “real understanding?” Do we have to symbolically “die” in order to awaken?

- The group of Seekers reunite and band together to cross the Gobi Desert and find the hidden scrolls. What is the value of having spiritual friends? Is it easier to be on a Path of Awakening with the support of others? What is the meaning of the sandstorm? What “storms” do you weather together with spiritual friends (balancing on stilts above the fray)? When the group comes to “dangerous territory,” someone dies for the cause. “I cannot ask you to go any further,” says the leader. “And now we must separate again, until one of us finds a way.” Must we face danger on the spiritual path? Ultimately, must we separate from our friends and brethren in order to find our own way?

- Gurdjieff speaks with an old dervish in Bokhara, Afghanistan. He asks, “Have you found what you are looking for?” Gurdjieff replies: “I have found nothing. I don’t know how to search. There is never any answer.” The dervish explains: “You will never find the answer by yourself…It [your spiritual quest] is a dangerous undertaking. You will be risking your life. But at the right moment, there will be a guide.” What does Gurdjieff’s search for the mythical Sarmoung Brotherhood represent to you and your Path? Do you even “know how to search?” What is the significance of a spiritual guide?

- When Gurdjieff meets Father Giovanni, the Christian missionary explains that “Faith cannot be given to men. Faith is not the result of thinking. It comes from direct knowledge…Thinking and knowing are quite different.” What is faith? What is the difference between “thinking” and “knowing”?

- As Gurdjieff gets closer to his Truth, he is hooded and is required to take an oath of secrecy in order to complete his journey. What’s the significance of a blinded spiritual seeker being led across rivers, through dense foliage, across deserts, and up very high mountain passes? Gurdjieff must balance carefully in order to cross a creaky, slatted wooden footbridge over a deep chasm and then continue on foot to reach the monastery. Have you ever feared falling on the road to spiritual fulfillment? What have been some of the dangers you have faced along the way? Has it been a precarious journey?

- The Prince shows Gurdjieff into the courtyard to witness “movements, dances, and exercises.” He explains that “We can read in them truths.” What do you make of these synchronized dances, vocalizations and movements?

- The Prince says to Gurdjieff: “You have now found the conditions in which the desire in your heart can become the reality of your being. Stay here until you acquire a force in you that nothing can destroy. Then you will need to go back into life, and there you will measure yourself constantly with forces that will show you your place.” Have you attained some form of spiritual awakening or contentment? How do you keep that force strong, so that “nothing can destroy” it? When you go “back into life” from retreat or practice time, how do you keep “your place” or your spiritual focus?

- The final scene seems to mirror the opening scene. Gurdjieff is dressed all in white, just like when he was a young boy. The music and rocky mountain landscape pay homage to the very beginning. It’s just Gurdjieff, all alone, full of wonder and awe at the world around him. What does this mean for our own journey? What is the truth of the beginning, middle and end? Do we wind up right where we started from? If so, how have things changed and what have we learned along the way?

We hope you are able to use this Viewer’s Guide to Meetings With Remarkable Men to help ease your own struggle and bring your own Awakening a little closer to reality. May the young Gurdjieff’s journey inspire your own!

The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell Now More Relevant Than Ever

Making sense of our consciousness can be difficult, and in our materialist, western world we try endlessly to objectify that experience. But over the course of the past century, there have been a number of intermediaries reminding us to reconnect with elements of the spiritual journey.

Names like Alan Watts, Thich Nhat Hanh, and Deepak Chopra have sparked a renaissance of interest in the nature of consciousness, meditation, and mindfulness. They remind us of stories and lessons learned over the course of our history, and within these, we find recurring themes of transcendent truth.

But there is one liaison between the old world and the new, who bridged these philosophies and connected the ancient esotericism of the east to the pragmatism of the scientific west, through archetypes and allegory.

Joseph Campbell defined this thirst for truth over a lifetime by examining artists, psychologists, writers, and philosophers. He referred to the lessons in their mythos as the Masks of God, and the protagonists within those stories as the Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Campbell consumed as much of their wisdom as possible, voraciously reading nine hours a day for years at a time. He absorbed the work of great western minds like Carl Jung, Pablo Picasso, James Joyce, and Sinclair Lewis. Through these lessons, he connected the dots of contemporary consciousness with the timeless teachings of the Bhagavad Gita, the Bible, Greek mythology, and the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

In those years of study, he found lessons that applied to man and society at large – overarching narratives that struck a universal chord, particularly the sense that at some point in our lives, we find there is a call unanswered, a void in the spirit that must be fulfilled.

“Follow your bliss and the universe will open doors for you where there were only walls. The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

– Joseph Campbell

The Hero’s Journey

Campbell said you can never be at peace with yourself if you do not answer that call. The call to adventure that forces the hero to remove himself from the ordinary world and face whatever it is that threatens his safety, comfort, and way of life.

At first, the call is refused when fears and second thoughts arise, or the comforts of the home seem too difficult to abandon. But eventually, the hero finds a mentor who pushes them and provides the tools needed to confront their tribulation.

When one considers the “Hero’s Journey,” Luke Skywalker, Arjuna, or even Hamlet could fit the role, but these stereotypes are meant to convey a general truth about finding the fulfillment we all seek. The personal ordeals that confront us can be difficult to face, causing us to relinquish a part of ourselves and take solace in a place that feels safe, while we remain oblivious to what could be learned by challenging those fears.

For some, it may be a vice; an addiction that keeps us trapped in some behavior or lifestyle. Campbell looked to the Tibetan Book of the Dead to confront this type of ordeal, learning that the scripture taught one to strive for the opposing virtue of whatever your vice may be; to overcome what he called the “inmost cave.” By cultivating the antithesis of your vice, you will find the self-actualization that defines your being.

This sentiment has been echoed many times over the ages, and Campbell summed it up when he said, “Gods suppressed become devils, and often it is these devils whom we first encounter when we turn inward.”