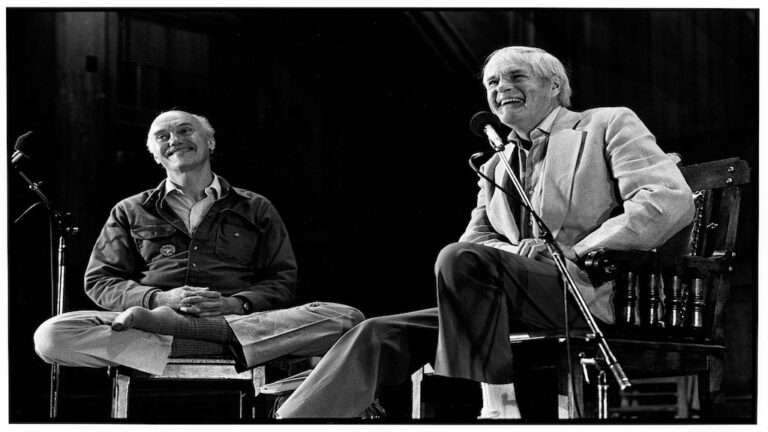

Ram Dass and Timothy Leary; A Friendship Beyond Space and Time

Friendships can be slippery things, often dependent on a particular time and place. But in the case of cultural icons Timothy Leary and Ram Dass, their friendship, while grounded very much in the times, also reached beyond them and influenced an entire generation of seekers.

“Dying to Know” explores Leary and Ram Dass’s long and complicated relationship, from their shared passion for pushing against societal norms to their ground-breaking work in understanding consciousness, and even how we approach our own death. Their friendship was one of the most influential and important, of our times.

From Very Different Beginnings

While both men were born in Massachusetts, their childhoods were very different. Leary, an only child, stemmed from a mix of Irish backgrounds with his mother being extremely conservative and his father, a wilder, drinking, roving type. As a child, Leary loved reading, drawn to stories of adventure and heroism.

Leary’s paternal grandfather advised him to follow his own path and to be “one of a kind.” This advice led him to challenge authority. In his college years, he would leave West Point after a dismissed court-martial charge for supplying alcohol to other cadets, then taking on the persona of the provocateur.

Ram Dass, aka Richard Alpert, was the son of a railroad president and founder of Brandeis University, growing up in a stable, middle-class Jewish family. Alpert graduated from Wesleyan University, then Stanford, where he served as faculty, as well as at the University of California, Berkeley. At 27 years old, he was appointed as an assistant professor to Harvard’s psychology department in 1958; Alpert was a rising success. But he was living a lie as a closeted homosexual. The cost of this secret, according to Alpert, “set the stage for feeling like an outcast.”

Leary also experienced early success in the academic world. His first book, The Interpersonal Diagnosis of Personality, was named “book of the year” in 1957 by the American Psychological Association and he was on the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley where he’d received his doctorate in psychology. Despite this academic success, his personal life was troubled. His first marriage ended tragically with his wife’s suicide, leaving Leary to raise their two children on his own.

Haunted by her death, Leary and his children moved to Florence, Italy, where he met David McClellan, the director of Harvard’s Center for Personality Research, who was so impressed by Leary’s original ideas on psychology, he offered him a three-year research project where Leary and Alpert’s paths would cosmically converge.

That same summer was also the first time Leary tried psychedelic mushrooms while traveling in Mexico, an experience in which Leary said he “learned more about his mind in four hours than he had in his 15 years as a psychologist.”

Kindred Consciousness

Leary focused his research efforts on the effects of psilocybin, at that time a legal substance obtained through Sandoz Pharmaceuticals. Trained staff members took the drug and acted as guides for the volunteers in an approach that became known as “set and setting.” When Leary arrived at Harvard, Alpert was drawn to Leary’s sense of personal and academic freedom, as well as his outlandish sense of humor.

Alpert saw his new friend as a visionary and believed Leary’s ability to “see outside the system” would allow Alpert to finally break free. With Leary’s guidance, Alpert tried synthetic psilocybin, the active ingredient in “magic” mushrooms. It was a profound experience that stripped him of his false identities.

In 1962, Leary’s research headed in a new direction with the introduction of LSD. At first, Leary was reluctant to expand his research, but after he explored the drug on his own, he changed his mind and the course of the project. Leary, and his research team, felt that the controlled use of LSD could free people to release themselves from the strict confines of society’s norms into a fuller existence. At a time when outer space was being aggressively explored, Leary and Alpert thought of themselves as inner cosmic adventurers or psychonauts.

At the height of the project, Alpert broke the rule regarding only graduate students being used as subjects leading to him being fired from Harvard while bringing national attention to psychedelics. Leary’s contract with Harvard was not renewed, as he and Alpert found a new way to continue their work.

The two resettled in Millbrook, New York on the expansive property of one of their subjects where they set up a new research site and a communal living environment known as Millbrook, and a second home to many of that era’s artists, thinkers, beat poets, and activists.

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out

At Millbrook, Alpert became “the support system for Timothy’s (revolutionary) vision,” efforts that ranged from raising money to housekeeping to substitute parenting — whatever was needed to keep the enterprise afloat. This came at a huge financial and psychological cost, as well as straining their friendship. Alpert found himself in the position of having to break free from Leary, leaving Millbrook in 1965 to embark on his own spiritual quest.

During this time, Leary married a second time and divorced, then got married for a third time to Rosemary Woodruff. Leary headed to Mexico with his children, and upon their return, Woodruff was found in possession of a small amount of cannabis. Taking responsibility, Leary was sentenced to more than 30 years in prison, which was later reduced to a charge of interstate transportation.

For a generation of youth yearning to break free from the strict social confines of the 1950s, LSD represented the keys to that freedom. Leary had been an early proponent of legalizing drugs for adults with stringent license requirements, even being called before Congress to testify on the subject. He believed the criminalization of these substances was directly in correlation to the availability of them. He was right — LSD became the drug of choice for the younger generation and Leary’s words, “Turn on, tune in, drop out,” its rallying cry.

Named by President Nixon as America’s “most dangerous man,” Leary was arrested again in 1970 and sentenced to a minimum-security facility for 10 years. He escaped jail and embarked on a fugitive’s life with his fourth wife, culminating in his capture in Afghanistan where he was then returned to prison for four years, including two in solitary confinement.

Desperate to get out of jail, Leary turned to state and federal evidence; he and his wife were put into the witness protection program under the names James and Nora Joyce and relocated to Santa Fe, New Mexico. The relationship soon ended, already under intense strain due to drug abuse, alcoholism, and estrangement.

During this tumultuous period in Leary’s life, Alpert was on a very different journey. Traveling in India, he encountered Neem Karoli Baba, also known as Maharaj-ji by his followers. He became Alpert’s guru and gave him the spiritual name, Ram Dass.

After an intensive period of studying yoga and meditation, Ram Dass returned to the United States a very changed man. He wrote about his experience in Be Here Now, one of the best-selling spiritual books of all time and considered many a spiritual seeker’s manual. Ram Dass emerged as a bridge between East and West, opening a new world of spiritual awakening to a generation hungry for ways to train and calm the mind.

A New Stage of Life and Friendship

The two men’s lives took very different paths, but it was through their personal encounter with their own mortality that a new connection was formed. For both, the illness became another opportunity to engage in the greatest mythical experience of all: death.

When Leary was diagnosed with advanced and inoperable prostate cancer in 1995, he turned to his old friend Ram Dass for support, wisdom, and guidance. Two decades before, Ram Dass established the Dying Project (with Stephen and Andrea Levine, and Dale Borglum) and was considered a pioneer in the field of conscious dying and hospice care. As with his life, Leary applied the same bravado to his cancer, which Ram Dass describes as a “theater piece, a poem, a dance…(it) was a celebratory moment.”

Leary died May 31, 1996. In speaking about Leary’s death, Ram Dass said, “Timothy and I are explorers, we’re beloveds, we’re deeply connected and I can’t imagine that will ever change.”

In 1997, Ram Dass experienced a stroke that left him with expressive aphasia and a massive cerebral hemorrhage, leaving him with what doctors predicted as a 10% chance of survival. He viewed this health challenge as an act of grace and spiritual practice, continuing to write, teach, and live with what Joan Halifax called a “delightful determination that is a model to us all.” Ram Dass died 23 years after his friend, also surrounded by loving friends and family.

From the spark that lit their friendship at Harvard, Dying to Know lovingly relates the story of a friendship that transcended time, space, culture, and for Leary and Ram Dass, their own physical realms. Their friendship did change the world, but it was also centered on the most important thing – love; a wild and crazy love that lasted a lifetime.

Qigong: Centuries Old Wisdom for Modern Times

Modern life is busy and stressful. The speed in which we live can be exhausting and the catalyst for a host of ailments. In our chronically overscheduled lives, learning to cultivate a sense of balance can be difficult. However, there is an ancient solution to this very modern problem: Qigong, a centuries-old method viewed as a way to find peace, balance, mindfulness and a way to tap into one’s life energy.

Originating in China, qigong is actively practiced around the globe by people of all ages; from those seeking increased flexibility, health, spirituality, improved posture, and ease of movement. What is qigong and how has this “life energy” form of exercise become such a popular form of self-care?

Qigong can best be described as a gentle form of martial arts that unites breathing, movement, and meditation. According to the National Qigong Association, qigong is not one form. It literally has hundreds of styles and applications, traditions, practices, and lineages. What is agreed upon is that, at its center, qigong is a philosophy based on two essential aspects: qi, the subtle breath or vital energy; and gong, a skill cultivated through steady practice working to stimulate our Meridian system.