Scientists Gave Octopuses Ecstasy To Study Social Behavior

Octopuses keep popping up in some pretty far-out studies, like the one that suggested our tentacled-friends may have hitched a ride on an interstellar comet, before crash landing on Earth. But a recent study decided to drug these panspermic alien ambassadors with a dose of MDMA – the empathogen more commonly known as ecstasy or molly – to see if octopuses get the same warm, cuddly reaction to the drug that we do.

And according to the recent paper published in Current Biology… they sure do.

The paper’s authors Gül Dölen and Eric Edsinger conducted the experiment in order to study serotonin’s role in the evolution of social behavior. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter produced in the brain, believed to contribute to feelings of well-being, happiness, and motivation – it’s what makes us want to interact with each other.

The complexity of an octopus brain is similar to ours in many ways, only having branched off from us about 500 million years ago on the evolutionary timeline. But the necessary cognitive systems – like a cortex and reward circuit – which give humans the sense of love, empathy, and connection, are missing in the cephalopod brain.

And while one might expect octopuses to be socialites, constantly probing everything with those noodley appendages, they are in fact asocial animals – not just antisocial, but asocial. The only time they interact with one another is to mate, otherwise they are completely hostile.

So, when scientists gave a test group of seven Octopus bimaculoides varying doses of MDMA, they were amazed to see them respond in much the same way a human would. Heavy doses made them turn white, but smaller doses seemed to evoke a sensation known colloquially among ravers as “rolling.” They became touchy-feely with other octopuses, they were interested in minor sounds and smells, one started doing flips, and one “looked like it was doing water ballet,” Dölen told Gizmodo.

Dölen and Edsinger said they were astonished – as were their peers in the world of biology, who said they never imagined a monoamine neurotransmitter could have the same effect on a vastly different animal brain structure.

In her recent New York Times Bestseller, The Soul of an Octopus, Sy Montgomery elucidated the world on the truly sentient nature of octopuses. Unbeknownst to many, octopuses are in fact highly aware, as each of their tentacles has its own complicated network of neurons, allowing for eight independently functioning limbs of taste, touch, and motor function. Add to that a massive brain, proportionate to its size, and you get one of the most intelligent creatures in the ocean.

MDMA is a schedule 1 substance in the U.S., meaning it has a high potential for abuse and low potential for medical application. However, this antiquated and misunderstood classification is slowly being reconsidered, as groups like MAPS have had success with clinical trials using it as a tool for psychotherapy.

This recent study could inform scientists on the way our brains have developed over the millions of years of evolution since splitting from cephalopods, in order to better understand social disorders, such as PTSD and autistic social anxiety.

And unlike other trials that involve animal testing, this seems like one the octopuses might actually enjoy.

Watch the feature documentary Neurons to Nirvana, which explores the resurgence of psychedelics as medicine in modern society:

Scientists Are Now Using Sound Waves to Regrow Bone Tissue

The future of regenerative medicine could be found within sound healing by regrowing bone cells with sound waves.

The use of sound as a healing modality has an ancient tradition all over the world. The ancient Greeks used sound to cure mental disorders; Australian Aborigines reportedly use the didgeridoo to heal; and Tibetan or Himalayan singing bowls were, and still are, used for spiritual healing ceremonies.

Recently, a study showed an hour-long sound bowl meditation reduced anger, fatigue, anxiety, and depression, which is great news for mental health. But now, a new study out of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia, showed physical healing using sound waves.

Scientists used high-frequency soundwaves to turn stem cells into bone cells in a medical discipline called ’tissue engineering,’ where the goal is to rebuild tissue and bone by helping the body to heal itself.

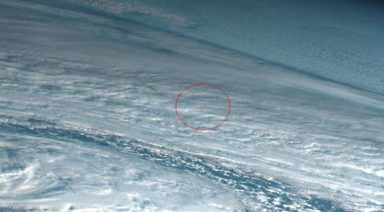

The researchers shot sound waves at tissue cells for 10 minutes a day over the course of five days. This magnified image shows stem cells turning into bone cells after being treated with high-frequency sound waves.