Star Child Skull Proved Human, But How Accurate Is DNA Testing?

DNA analysis is widely considered to be the be-all, end-all when it comes to forensic analysis, whether criminal or archeological. The level of technology that we have to sequence DNA is considered highly accurate and can tell us quite a bit about what happened to an organism, even if it is hundreds or thousands of years old. But even if DNA sequencing can pinpoint gender, age and lineage to a high degree of accuracy, getting an authentic sample that isn’t contaminated can be incredibly difficult.

Can DNA Testing Be Wrong?

DNA evidence became popular in criminal cases starting in the 80’s, particularly in the O.J. Simpson trial. DNA tests were considered to be the most conclusive variable in a criminal trial, being the nail in the coffin that could no longer be argued. Until it came to light that a number of labs had made mistakes, leading to wrongful accusations and prison sentences for innocent people, often ruining their lives. So, what happened that led to this epiphany that DNA tests weren’t foolproof?

For a DNA sequencing to be accurate, there are certain criteria that need to be met. You need a large, well-preserved sample of the subject’s DNA, it must be clear how the subject’s DNA arrived at the scene it was found, and the lab must not make any mistakes. If all three of these criteria are met, you should get a pretty accurate result, but meeting them can be incredibly difficult.

In DNA sequencing of humans, a lab doesn’t map the human genome, rather it looks at 13-14 different loci in our genes. Each locus contains two alleles, one inherited from each parent. These alleles differ from person to person, though we share half or more with relatives. It is rare to share more than a few with strangers, making it relatively easy to figure out the lineage of your sample. That is if the DNA samples remain intact and do not break down.

How Accurate Are Archeological DNA Tests?

When it comes to archeology, DNA testing can become more difficult due to the history of your sample and the fact that it has probably been dead for many years. In the process of unearthing a sample and getting it to a lab for testing, there are plenty of steps along the way where it can become contaminated, ranging from: sample collection, shipping, any time its removed from storage and put back into storage, and whenever it’s being tested. Not to mention, who knows whether contamination occurred before the burial or before it was discovered by the archeologist.

Contemporary DNA can easily contaminate a sample, from the archeologist all the way to the lab, sometimes making it nearly impossible for the DNA sequencer to tell the difference between modern and ancient DNA, or aDNA, and this tends to happen often with ancient human material. Even if a sample was contaminated decades ago, it could show the same signs of DNA degradation that would be seen in aDNA patterns. Another issue that is common with aDNA, is the issue of postmortem mutations that increase over time, damaging the DNA from environmental factors.

So, what can be done to prevent contamination from occurring? A laboratory with a well-trained scientist will typically assume that any specimen sent to them has probably been contaminated and will take the necessary steps to remove the contaminated DNA. Usually through a chemical process, the scientist can remove recent contamination, though older DNA can be more difficult.

The Starchild Skull Final DNA Results

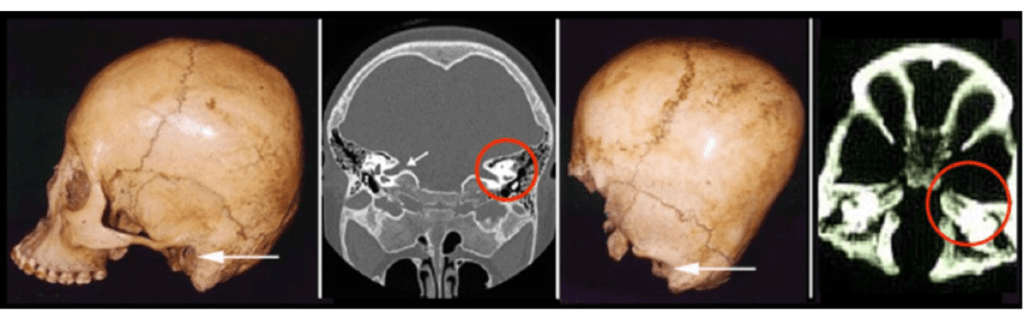

Recently, a final report was released that gave the definitive results on the abnormally shaped “Starchild skull.” The skull, which was found in Delicias, Mexico, has confounded researchers for years, due to its oddly-shaped head that seemed to defy any known human deformities. Having been found in an old mine next to a normal human skeleton, there has been conjecture over whether the Starchild could be an alien-human hybrid, or whether it’s simply a deformed child.

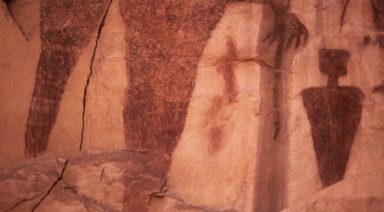

Regular ear canal vs Starchild ear canal

The skull however, showed variations from known mutations and abnormalities like hydrocephaly, such as the lack of the inion region of the skull and the complete flattening of the back of the cranium. Some proposed the theory that the flattening may have come from a practice known as cradle-boarding, though the flattening is significantly more extensive compared to any other skull that had been cradle-boarded. Also, to achieve this level of flattening by cradle-boarding, the child would have been asphyxiated.

The Starchild skull was dated to be 900 years old, while appearing to be around the age of five when it died. Aside from the bulbous cranium, the skull showed shallow, close-set eye sockets that were broken, along with a completely broken and missing jaw. The skull retained its teeth, allowing for an examination from a dentist who helped determine its age.

In 2003, mitochondrial-DNA testing showed that half of its DNA came from the haplogroup C1 – a genetic makeup that originates in Asia near the Caspian Sea, but which is also common to Native Americans whose ancestors probably migrated over the land bridge.

The skull is said to have been found in the 1930s and has changed possession many times since. It has also been examined by numerous scientists, before being subjected to DNA sequencing. In addition, the skull has been polished, varnished, lacquered and cleaned numerous times over the years, all of which doesn’t help in maintaining a sample from which an accurate drawing of DNA could be harvested.

But the most recent tests on the skull have concluded that it is 100 percent human. The paternal half of its genetic origin was said to come from the haplogroup Q which is determinant of Native Americans from South America. Chase Kloetzke and Kerry McClure, the two researchers who were responsible for finalizing the results, have conceded that they believe it is human based on these results. Though they admittedly wanted it to be of extraterrestrial origin and claim they believe the government is covering up knowledge of an extraterrestrial presence, they believe that the Starchild skull came from a deformed human child.

starchild vs average human skull via ancient-origins.com

But what about contamination? Neither Kloetzke, nor McClure mention that their results could have been contaminated, though the results from the DNA lab include it as a possibility. Written clearly on the results page posted on their website, the lab states:

“The combination of replication procedures in place for laboratory sterilization and elimination of Paleo-DNA Laboratory DNA profiles suggest the results are authentic and not contamination. However, no modern comparison samples were submitted with this batch from the archeologists or any other individual who may have handled the sample and potentially contaminated it. Therefore, we cannot guarantee that these profiles are authentic and not a previous handler.”

Could their results be the DNA of someone else with haplogroup C and Q mitochondrial DNA? If the skull had been sitting in Mexico for 900 years, buried shallowly beneath the surface and eventually found in a mine, the chances are pretty good that someone else’s DNA of similar lineage could have wound up on the skull. Not to mention the number of handlers who have touched it since its supposed discovery in the 1930s. Despite the difficulty in tracking down all of the people who have touched it since then, it would have been relatively easy to at least test it against the DNA of those who were known to have touched it.

So, despite the high level of accuracy of DNA sequencing with a legitimate sample, can DNA tests be wrong? The answer is yes, because there are plenty of opportunities for a sample to become contaminated. But despite these possibilities of contamination, it appears that the case has been closed, at least for now, on the ethnic provenance of the Starchild. Or has it?

Who Were the Ancient Race of Red Haired Giants?

Legends of giants exist around the world and some say they have even found evidence, but mainstream science dismisses giants as a hoax. Is it time for a fresh look at ancient giants?

Giants have been dismissed by science and archeology as a myth but are embraced by many cultures around the world. Globally, there are even structures that would fit the giant narrative, but perhaps most importantly, oral histories, folklore, and even scripture mention giants.

Jack Cary, researcher and author of “Paranormal Planet” has studied this phenomenon for years.

“Indigenous people throughout the entire planet have these oral histories of red-haired giants. And there are a lot of indications and clues as to who the giants were and where they originated,” Cary said.

“One of the most important is Genesis 6:4 in which it describes that the Nephilim were on Earth, they had children by human women, these children were giants…”