Suicide and the Superficial Self

Have you ever thought of committing suicide? It’s okay if you have. In fact, I’d venture to say that it’s a fairly normal thing for most people to have considered at some point in their life – at least in the theoretical sense of it. To consider what it may actually take to go through with it, or what it may actually mean that you would want to. If you’re like me, you may even have occupied that place where it seemed to be a real option; and, like me, actually taken that option a number of times, in a manner of speaking.

When a famous person, someone we know, or someone we’ve just been acquainted with commits suicide, naturally there’s the sadness that accompanies such a profound personal tragedy, followed by that sense of futility. But there may also be a deep, underlying identification with a troubled fellow voyager; the understanding of suicide as a viable solution to what seems to be an utterly hopeless situation.

“When you commit suicide, you’re killing the wrong person.”

Anonymous

Obviously, I didn’t really commit suicide when I thought of it, but having passed through that “dark night of the soul,” I do understand the impulse – and not as an overwhelming urge to for the absolute, but instead as an overwhelming urge for absolution.

The Urge for Absolution

After all, the desire to ‘end it all’ often isn’t a wish to actually die, just a wish to end things the way they are.

In this sense, the suicide urge is a completely natural impulse that arises simultaneously from both deep despair and a kind of optimism in the eternal, the idea that a spiritual solution awaits our return. We’re searching for the source of relief, renewal, and regeneration.

It can actually indicate a profound kind of spiritual sanity and practical wisdom – the desire to return our battered soul into the care of a loving power, and rediscover our spiritual freedom, away from a world where our human shortcomings and ineffectiveness are constantly imposed on our simple search for happiness.

But please – don’t get me wrong on this point!

I’m not urging anyone to commit suicide. At least not in the way you may usually think of it.

Our misunderstanding of the suicide ‘process’ has a lot to do with our unwillingness to properly define death itself. As a person who’s unintentionally experienced a kind of reincarnation myself, I can tell you that we do live and die many times over–and not just in the physical sense of it.

For example, the child you once were – that innocent, playful, awakening soul – died outwardly in a sense, when the need to create an egoic interface to “the grown-up world” (and biological chemistry) raised its ugly head, all too soon. Likewise, your teenager was sacrificed to the demands of a life of responsibility. And as you get older, the young adult you once were has given way to a being of lesser physical ability (that’s one I really miss). The body I’m in now is heading down a stretch of road dotted with signposts for another turn-off up ahead. There’s always some form of death approaching. That’s just the way it is.

“Without dying to the world of the old order, there is no place for renewal, because…it is illusory to hope that growth is but an additive process requiring neither sacrifice nor death. The soul favors the death experience to usher in change. Viewed this way, the suicide impulse is a transformational drive.”

James Hillman

Suicide and the Soul

The author of that quote, James Hillman, (my late uncle, by marriage), was a brilliant (and very funny) guy – a teacher, author, Jungian analyst, former director of the Jung Institute in Zurich, and the creator of Archetypal Psychology. That quote is from his elegant, utterly amazing little book, Suicide and the Soul (Harper Colophon, 1964), in which he describes a lot of what I’m talking about here far more eloquently than I ever could, based on years of working with patients in states of personal crisis. Elsewhere in the book, he says,

“To put an ‘end to one’s life’ means to come to one’s end, to find the end or limit of what one is, in order to arrive at what one is not – yet.”

James Hillman

Personally, this required a number of very uncomfortable moments in my own life, where who and what “I thought I was,” lay in broken pieces on the ground before me. When my life, as it was, no longer made any sense – where it no longer worked. The person I was had stopped being a viably effective participant, and living that way doomed me to repetitive collisions with my own self-created obstacles to happiness and fulfillment. That’s a dark place, where the suicidal impulse arises. Naturally, I required a deliverance – a death – to make room for my own personal renewal.

So, I committed a kind of suicide – and I’ve done it a few times – the sort that I propose you embrace if you ever reach that impasse yourself. Not to actually physically kill yourself, but to set about killing the part of you that no longer works.

That false egoic interface – often the same one we constructed first as kids – has to be destroyed to allow a more authentic self to emerge and arise from the ashes like the mythical phoenix. That’s an archetype Uncle James may have liked.

While my late uncle speaks metaphorically, as an analyst, I speak as a ‘near death experiencer,’ so in what I know as a real, spiritual sense, we do live and die and live and die – on and on. Our deaths are necessary for our soul’s growth; every death is a suicide, of sorts, fashioned over time by our own designs. Life can be quite ruthless in pointing out the biggest flaws in those designs, but the awareness we gain is the gift that pain gives us. It becomes our job to change. This is the case at every level.

Fractal Motivation

We are all the creators of our own deaths, individually and collectively, and the suicide urge itself is a kind of fractal motivation – an urge that lives within every expression of consciousness taking part in our mysterious spiritual evolution. From plants, to animals, to us, to our earth, there is that sacrifice to growth, to our return, imprinted in our very core.

Meanwhile, our soul – the same playful soul of a child – continues to live on in wonder, willingness, and absolute surrender, even as we must slough off sheaths of outer lives. With that willingness, that faith, we can sacrifice our overly serious superficial selves; with our soul’s knowledge that our true self is never abandoned, we can bury “who we were supposed to be”– even if we don’t know who we are meant to become yet. It’s an uncomfortable state of grace, like the chaotic mess inside a chrysalis just before a butterfly emerges.

Kill the Right Person

So, please, don’t ever actually kill yourself – it’s a “permanent solution to a temporary problem.” But if you insist on it, make sure you kill the right person. Kill only the part of yourself that causes pain; the part that prevents you from being the creature of light and love you are truly meant to be. Bury your superficial self, christen a more authentic you, rise up, and spread your new wings.

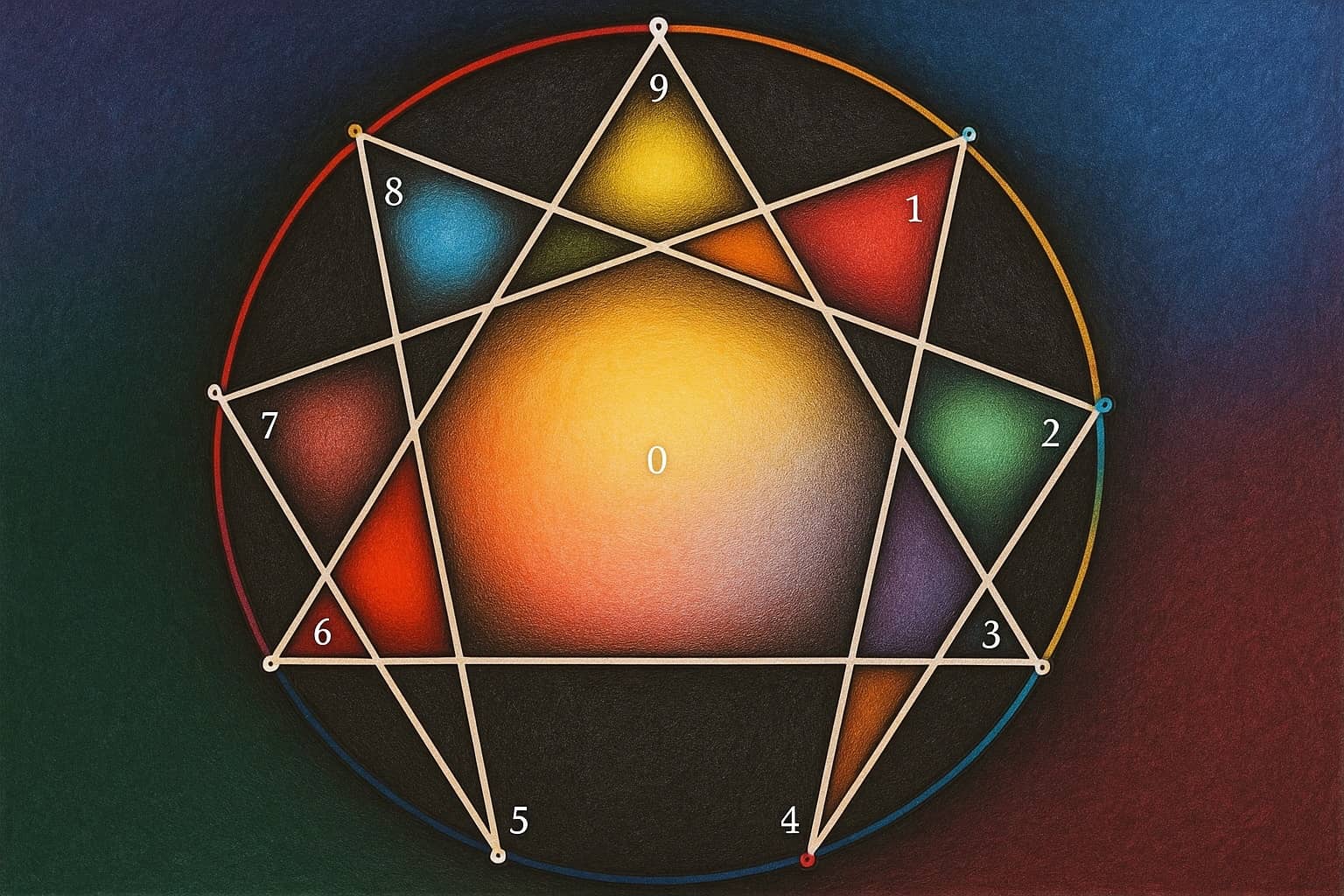

What the Enneagram Is and How to Identify Your Dominant Enneatype

The Enneagram is a tool for self-knowledge that describes nine personality types, each with a particular way of thinking, feeling, and relating to the world. Its purpose is to help us understand our deepest motivations and the unconscious patterns that shape our lives. In this article, we explore what the Enneagram is, how it works, and how you can discover your dominant Enneatype to better understand yourself and grow as a person.

Table of Contents

- What Is the Enneagram of Personality?

- What Are the Enneatypes and How Are They Classified?

- What Are Wings in the Enneagram and How Do They Influence Us?

- What Does the Enneagram Symbol Represent?

- How to Discover Your Dominant Enneatype

- Self-Knowledge Through the Enneagram

- The History and Origin of the Enneagram

What Is the Enneagram of Personality?

The Enneagram is a system of self-knowledge that organizes human personality into nine main behavioral patterns, known as Enneatypes. Each person tends to live from one of these nine styles, which form during childhood as a response to an emotional wound. From there, we develop a personality that attempts to compensate for that pain, repeating beliefs, attitudes, and reactions we rarely question.

The word “Enneagram” comes from Greek and means “nine lines,” referring to the symbol that represents it. This symbol shows how the nine types relate to each other and helps us understand the changes we experience when we are emotionally balanced or unbalanced. The Enneagram is not a personality test, but rather a map that explains our automatic reactions and the psychological roots behind them.

The most valuable aspect of the Enneagram is that it not only reveals our defense mechanisms but also our potential for transformation. By identifying our dominant Enneatype, we can understand what limits us, what drives us, and what we need to evolve. For this reason, this tool is increasingly used in personal, therapeutic, educational, and professional development processes.

What Are the Enneatypes and How Are They Classified?

The Enneatypes are the nine personality types described by the Enneagram. Each one emerges from an emotional wound that shapes how we see the world and relate to others. These psychological structures are not rigid labels, but rather defense mechanisms developed in childhood to feel safe, loved, or valued. Knowing our dominant Enneatype allows us to understand what deeply motivates us, what our core fears are, and which patterns we tend to repeat unconsciously. Below, we describe each of the 9 Enneatypes in the Enneagram.

- Enneatype 1 (The Perfectionist): Their core wound is the belief that they are not good enough. To compensate, they constantly strive to do things “right,” following strict rules and high standards. They are usually responsible, ethical, and committed, but can also be rigid, critical, and prone to frustration when things don’t go as expected.

- Enneatype 2 (The Helper): They believe they must earn love by serving others. They devote themselves to caring, supporting, and being available, hoping for affection in return. While generous and empathetic, they can fall into emotional dependency and manipulative behaviors when they don’t feel appreciated.

- Enneatype 3 (The Achiever): They fear they are not worthy unless they prove their success or accomplishments. Their self-esteem is tied to performance and how others perceive them. Often efficient, ambitious, and charismatic, they may lose authenticity by adapting to expectations and avoiding vulnerability.

- Enneatype 4 (The Individualist): Their wound is the feeling of not being enough just as they are. They seek to stand out by being unique, special, and different. They experience emotions intensely and often feel misunderstood, which can lead to melancholy, envy, and disconnection from the present.

- Enneatype 5 (The Observer): Their main fear is not being able to cope with emotional demands. To protect themselves, they retreat into their minds, knowledge, and isolation. Analytical, independent, and intellectual, they may also be distant and disconnected from emotions and human contact.

- Enneatype 6 (The Loyalist): Their wound is rooted in mistrust of themselves and the world around them. They live in a state of alertness, anticipating danger and seeking certainty. Loyal, responsible, and cooperative, they can also be anxious, indecisive, and prone to relying on authority figures for guidance.

- Enneatype 7 (The Enthusiast): They avoid pain and discomfort by constantly seeking positive stimulation. They fill their schedules with plans, activities, and distractions to avoid confronting inner emptiness. Cheerful, versatile, and optimistic, they can also be inconsistent, superficial, and escapist.

- Enneatype 8 (The Challenger): They fear being hurt or controlled by others, so they adopt a stance of strength and dominance. They protect themselves by showing authority, confidence, and determination. While they can be leaders, protectors, and just, they may also come across as authoritarian, aggressive, and resistant to vulnerability.

- Enneatype 9 (The Peacemaker): Their wound lies in the fear of conflict and rejection from others. They tend to minimize themselves, avoid confrontations, and adapt to avoid discomfort. Calm, kind, and conciliatory, they may also be passive, disconnected from their desires, and struggle with decision-making.

What Are Wings in the Enneagram and How Do They Influence Us?

Within the Enneagram, each Enneatype is connected to the two neighboring types on the circle. These are known as “wings.” For example, someone whose dominant Enneatype is 5 may have a wing 4 or a wing 6. These wings don’t change the core type, but they do nuance our personality by adding secondary characteristics that broaden or balance our traits.

The influence of wings can be very strong or barely noticeable, depending on each person’s level of personal development. Some people clearly identify with one of the two wings, while others display traits from both. Wings function as extensions of the main type and often bring in abilities or resources that help compensate for certain limitations of the dominant Enneatype.

Understanding our wings not only deepens self-awareness, but also helps us better understand our inner contradictions. Through them, we can observe how our personality adapts, how we blend different traits, and how we expand our ways of responding to situations. Identifying the role of our wings is a key step toward working on ourselves with more consciousness and flexibility.

What Does the Enneagram Symbol Represent?

The Enneagram symbol is a geometric figure made up of a circle, an equilateral triangle, and a six-pointed irregular line. At first glance, it may seem complex, but each part has a deep meaning that helps us understand how this system works. The nine points around the circle represent the nine Enneatypes, and their placement is not random—they reflect a logical order related to energy and transformation.

The triangle connects points 3, 6, and 9, forming what is known as the “inner triad.” This shape represents three fundamental forces in the human being: action, emotion, and thought. The six-pointed figure (connecting points 1-4-2-8-5-7) illustrates the internal movement between types, showing how we shift depending on our level of balance or stress. This dynamic pattern is key to understanding growth or stagnation within each personality.

Beyond its shape, this diagram shows that we are in constant transformation as human beings. Rather than labeling us, the symbol invites us to see that we are always evolving—either growing or getting stuck. Visualizing how the Enneatypes relate to each other allows us to better understand our inner transitions and the possible paths for conscious evolution.

How to Discover Your Dominant Enneatype

Discovering your dominant Enneatype is not about taking a simple quiz, but about observing with honesty your most frequent emotional, mental, and behavioral patterns. While questionnaires can help point you in the right direction, true understanding comes when you recognize yourself in the description of a type—especially in its core emotional wound. Identifying the type that reflects your deepest motivations and defense mechanisms is a personal process that requires reflection and sincerity.

A good starting point is to carefully read through the descriptions of the nine Enneatypes, paying attention to what makes you uncomfortable or resonates with you intensely. It’s not just about identifying external behaviors, but about detecting the inner need that drives your actions. Are you seeking approval, control, security, freedom? Observing how you react to conflict, failure, or criticism can offer valuable clues about your primary type.

It can also be helpful to complement this process with books, courses, or professional guidance. Therapists and coaches trained in the Enneagram can support your self-discovery in a more structured way. As you gain a clearer understanding of your type, you can begin working on your blind spots, reconnect with your most authentic self, and move toward a more conscious and liberated version of who you are.

Self-Knowledge Through the Enneagram

The Enneagram is not a system for labeling people, but rather a tool for understanding how we disconnect from our essence and how we can return to it. It helps us clearly see the unconscious patterns we’ve repeated for years—often the source of suffering, conflict, or frustration. By identifying our Enneatype, we gain the opportunity to stop acting on autopilot and begin making choices from a more conscious place.

The self-knowledge process that the Enneagram proposes is neither immediate nor linear. It involves peeling back layers of self-deception, acknowledging emotional wounds, and observing our defensive behaviors with compassion. It also invites us to reconnect with our essential virtues—qualities that already live within us, but which we’ve often forgotten or suppressed out of fear. This journey is not about perfection, but about authenticity and balance.

Knowing yourself through the Enneagram involves a commitment to personal growth and greater emotional responsibility. As we understand ourselves better, we also learn to understand others. This model offers a shared language to speak about the human experience—with all its light and shadow—and reminds us that beyond personality types, we all share the same longing: to live with more awareness, freedom, and meaning.

The History and Origin of the Enneagram

The origin of the Enneagram is complex, combining philosophical, spiritual, and psychological influences. While its symbol has ancient roots tracing back to Middle Eastern traditions and Sufism, its modern application to the study of personality began in the 20th century. It was the Bolivian mystic Óscar Ichazo who first structured the nine character types into a coherent system, integrating knowledge from various traditions and philosophical schools.

Later, Chilean psychiatrist Claudio Naranjo developed the model from a therapeutic perspective, incorporating concepts from Western psychology. Through his clinical experience, he outlined the traits and defense mechanisms of each type, allowing it to be applied in educational and psychological settings. His contribution was key to transforming the Enneagram into a practical tool for self-discovery. In recent decades, its use has expanded and gained popularity around the world.