Was Marilyn Monroe Killed to Prevent UFO Disclosure?

When famous model and film icon Marilyn Monroe was found dead in her home in 1962, the official autopsy reports labeled her death a barbiturate overdose, and likely the result of suicide.

While Monroe had exhibited signs of depression and used prescription sedatives for years, her death came at the peak of her career and was a shock to millions. And rightfully so, as Monroe was closely connected to a number of powerful men, namely President John F. Kennedy.

A number of conspiracies abound around her death, including the possibility that she was murdered by either the CIA or the mob out of spite of President Kennedy. Others thought that (then) Attorney General Robert Kennedy, had her killed because she had incriminating evidence against the family that could have ruined their political careers and led to legal woes.

But there’s another theory behind her untimely death that stands out above the rest—one that involves disclosure.

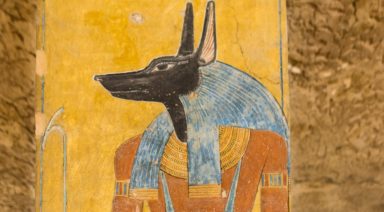

Based on a top-secret, classified document taken from a vault at the NSA, Dr. Steven Greer says he has reason to believe Monroe was killed because she was going to tell the world about the spacecraft recovered in New Mexico.

According to Dr. Greer, an insider he was connected to mailed him a copy of this document signed by James Jesus Angleton the chief of counterintelligence for the CIA from 1954 to 1975.

The document describes a wiretap placed on Monroe and details her discussion with a friend in New York, in which she allegedly said she was going to hold a press conference to disclose what President Kennedy had told her about “objects from outer space recovered from New Mexico in the 1940s.”

Dr. Greer said he even spoke to one of Monroe’s close friends in the film industry, actor and singer Burl Ives, who said the cause of her death wasn’t suicide, but that he believed this could have been a likely scenario.

But what exactly did President Kennedy tell Monroe and would the world have believed her if she went public? Could Kennedy’s assassination years later also have had something to do with his desire to disclose this information to the public?

More details to this bizarre story and the layers of government secrecy are revealed in a new 10-part special “Disclosure with Dr. Steven Greer.

Controversial Characteristics of Fractional Reserve Banking

Chances are, if everyone at your bank decided to withdraw the entirety of each of their bank accounts, the bank would not have enough money at its disposal to meet the demand. This is because banks commonly operate under a fractional reserve banking system. In other words, the bank uses your money however it wants, banking (ahem) on the fact that its account holders won’t protest. Unfair? It sure sounds like it. Stealing? The banks prefer to call it “borrowing.”

What Is Fractional Reserve Banking?

Many people believe that when they deposit money into a bank, the bank keeps all of their money on hand, in a vault, in cash. But this isn’t the way most banks work. According to Investopedia.com, fractional reserve banking refers to a system where banks only back a fraction of bank deposits with actual cash on-hand, available for immediate withdrawal.

This means only a fraction of the money you deposit into your account is required to be available for withdrawal at any given time. For most banks, that fraction is a mere 10 percent of your deposit. So, instead of putting $100 into the vault when you deposit a $100 check, only $10 goes in. That $10 is known as “reserves.”

Surprisingly, many banks are not required to even keep 10 percent on hand — and some aren’t required to keep any reserves at all. Any bank with less than $15.2 million in assets is exempt from keeping any reserves, and those with assets between $15.2 million and $110.2 million are only required to keep 3 percent.

There is an incentive, though, for your bank to keep more of your money in the vault: The Federal Reserve pays out interest on all reserves and excess reserves. The interest is called IOR (“Interest On Reserves”) or IOER (“Interest On Excess Reserves”), and since 2009, it pays out 0.25% at an annual rate.