Olmec Colossal Heads: What Are They?

Many ancient civilizations left behind intrigue even archaeologists still puzzle over today. In South America alone, we see cases of anomalous disappearances and unexplained history such as the Incas’ abandoned citadel, Machu Picchu, and the mysterious Mayans’ disappearance, which continue providing fodder for questions about what really happened to these societies.

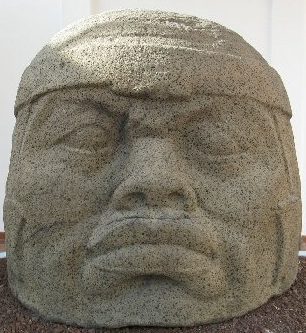

When it comes to the Olmec people, one giant factor continues to be debated: their colossal heads.

Not of the people themselves, but the 8-ton sculptures of heads they buried underground. The Olmec heads have become yet another famous and mysterious element of ancient cultures we just haven’t solved yet.

Olmec People and Civilization

The Olmec people lived in Southeastern Mexico between 1,500 and 400 B.C., in the lowlands of what is today Tabasco and Veracruz. They are credited with being the first civilization to develop in Mesoamerica, with the Olmec heartland being one of the six cradles of civilization.

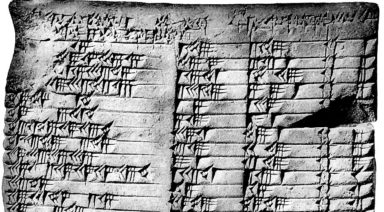

Olmecs were the first inhabitants of the Americas to settle in towns and cities with monumental architecture. Evidence has also been found for Olmec hieroglyphs around 650 B.C., as well as scripts on roller stamps and stone artifacts. The fine Olmec artwork survived in several ways, including figurines, sculptures, and of course, the colossal heads.

While the Olmecs seem to have been well-established tradesmen with routes, the civilization vanished around 300 B.C. , although its influence is obvious in the Mayan and Aztec civilizations that followed.

Olmec Colossal Heads

The Olmec colossal heads are aptly named — of the 17 uncovered in the region, the average weight is around 8 tons, standing three meters tall and four and a half meters circumference. Perhaps more than any other aspect of the Olmec heads, their size is cause for a great deal of analysis and speculation.

The heads were carved from a single basalt boulder retrieved from Cerro Cintepec in the Tuxtla Mountains. After their creation, the heads were then transported 100 kilometers to their final destination where they were buried. Most of the heads are wearing a protective helmet, which was worn by the Olmec during battle and the Mesoamerican ballgame, and it is likely they were originally painted with bright colors.

While the heads have been dated to either the Early Preclassic period (1500–1000 BC) and the Middle Preclassic (1000–400 BC) period, it is difficult to say for sure, given that many were removed from their prior contexts before archaeological excavation.

What Was the Heads’ Purpose?

Although the reason why the Olmec created the colossal heads remains unclear, there are many theories.

Because all of the heads have different facial features, they could be portraits of the rulers, as scholar M.E. Miller identified one of the heads to be the second-millennium BCE ruler of San Lorenzo. Miller posits this could have been an act of remembrance following that ruler’s death.

Conversely, the heads may have been defaced and buried by subsequent rulers to more strongly legitimize their claim to power.

Other theories suggest perhaps the figures were famous ball-court players, with the reasoning that the flattened noses and grimaces on the faces of the heads reflected the highly aggressive sport.

Heads From the Different Sites

Whatever the purpose of the heads, they were left underground for 3,000 years until the first head was re-discovered in 1871 CE, with the most recent excavation in 1994 CE.

The 17 heads were found across three sites in Mexico: La Venta, Tres Zapotes, and San Lorenzo.

La Venta

La Venta Head courtesy AncientWisdom.com

Heads found at La Venta all faced the Atlantic, with the largest flattened so as to also function as an altar. The speaking tube from the mouth to the ear was considered possible oracles or talking gods.

The large size and weight of the heads open up questions as to how the Olmec moved them from where they obtained the stone over 80 kilometers away.

Tres Zapotes

Image Source: AncientWisdom.com

The first head was found in 1938 by Dr. Stirling, who noted it was both realistic and negroid in character.

San Lorenzo

Image Source: AncientWisdom.com

Ten of the 17 heads have been found at San Lorenzo, arranged in a plaza with red sand and yellow gravel.

The Mystery Remains

The Olmec civilization proves similar to many others that developed in Latin America, in that they left behind intriguing clues that still have not been solved.

Colossal heads found buried in the former Olmec cradle of civilization raise interesting questions about the culture and technological capacity of the Olmec people.

Additionally, the Olmec heads are not an entirely unique phenomenon. The heads of Easter Island, Mt. Nemrut, and the underwater heads of Egypt all bear resemblance to the Olmec heads, despite all of these being scattered around the world.

Along with their influence upon the civilizations that followed, the Olmecs’ colossal heads give contemporary archaeologists and history enthusiasts alike plenty of questions to continue pondering.

Doggerland; Sunken Landmass Between UK & Europe May Be Atlantis

A thriving ancient culture that was wiped out by rising waters and a great tsunami—could the real Atlantis have been located between Britain and Europe?

Along the coast of the Netherlands, the ocean has been giving up its secrets. About 10,000 years ago, what is now water, was a landmass filled with flora, fresh game, and from what we can tell, a flourishing civilization. But at the end of the last ice age, glaciers melted, sea levels rose and what remained of this area is believed to have been knocked out by a tsunami.

Dubbed “Doggerland” after a sandbank off the coast of England, archeologists first learned of the potential of the Stone Age civilization there in 1931, when a fishing boat pulled up a barbed antler spearhead. There has been interest in Doggerland since then, but only in the last decade or so has there been intense study using high-tech seafloor mapping equipment, and low-tech citizen archeologists who bring their finds to the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, Holland.

Fishermen have found the remains of mammoths, hyenas, lions, as well as pre-historic tools, weapons, and skull fragments. Could this be the Atlantis that Plato wrote about? Some experts disagree…