Yoga Anatomy: Reducing Shoulder Impingement

![]()

![]()

Our wonderful shoulders are the most mobile joints in the body and, for anyone who has done any amount of Hatha Yoga flow, we can appreciate how much the shoulders are engaged and challenged in our practices. Given how frequently we load and stress the shoulders in yoga, it is ideal to move the shoulders with intelligence, mindfulness, and attentive care. One aspect of mindful movement and engagement is reducing the onset of shoulder impingement.

Our shoulder joints are made from a ‘ball and socket’ design. The upper arm bone (humerus) has defined structures at its proximal end (closest point to the center of the body). At the proximal end of the shaft, we see that the humerus has boney processes (called tubercles where tendons attach). Moving towards the shoulder joint, the humerus has a neck that transitions into a ‘head’ or the ball portion of the joint. The humeral head inserts into the socket (glenoid fossa or cavity) forming this highly moveable joint. The socket is part of the shoulder blade (scapula bone). There is another part of the shoulder blade with a boney projection called the acromion process which is positioned above the humerus. You call feel the acromion process on yourself by taking one hand over and to the back of the shoulder blade. Run your fingers along the shoulder blade to find a horizontal line of bone – this the spine of the scapula. Run your fingers all the way to the end into your shoulder – where this ends is your acromion process.

Between the acromion process and the tubercle region of the humerus is the ‘subacromial space.’ This is where our attention goes regarding shoulder impingement considerations. Deep above the spine of the scapula runs one of your rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus muscle), which has its tendon traveling through the subacromial space and attaching onto the greater tubercle of the humerus. To offer some protection to this tendon, there is a small sac of fluid (bursa sac) between the tendon and the acromion process.

When we stand in Mountain pose (arms relaxed), there is ample space in the subacromial space for the supraspinatus tendon and the bursa sac. When we lift our upper arm bone outwards (abduction) or towards certain angles of significant forward movement (flexion), the humerus closes into the subacromial space. For some people, due to bone structure and reduced subacromial space, they are more prone to having the tendon and/or bursa sac being compressed and stressed (aka shoulder impingement). With frequent compression, the tendon and/or bursa sac may develop conditions of inflammation. As with any acute or chronic development of shoulder impingement conditions, you will want to consult a qualified health professional for proper assessment and therapeutic treatment.

TRY THESE TECHNIQUES

Knowing the potential for shoulder impingement, we can apply a couple of movement techniques to retain more subacromial space and reduce compression and stress going into the tendon and bursa sac.

External Rotation

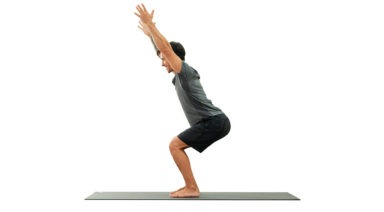

The first movement application is external rotation of the humerus, when you abduct and/or deeply flex the shoulder joint. When the upper arm bone internally rotates during abduction and/or flexion, the greater tubercle moves more closely into the subacromial space thus increasing the potential for impingement. When we externally rotate the upper arm bone, it shifts this boney process somewhat away leaving more space for the supraspinatus tendon and bursa sac.

Upwards Rotation

The second movement we can employ is scapular upwards rotation. The shoulder blade can be taken through 6 movements – one of them is an upwards rotation. When we significantly abduct or flex the shoulder joint, we want the shoulder blade to move with the upper arm bone (this is called scapulohumeral rhythm). Besides sustaining more fluid joint congruency and connection during these arm movements, maintaining this joint rhythm reduces the onset of shoulder impingement. Upwards rotation of the scapula is similar to a spinning movement of the shoulder blades away from the spine causing the socket and acromion process (all connected as one bone) to tilt upwards. The upwards lift of the acromion retains space in the subacromial space as the arm bone lifts through abduction or flexion.

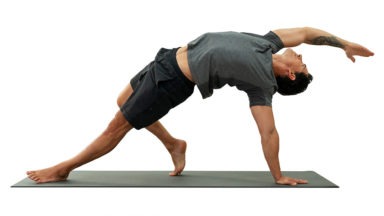

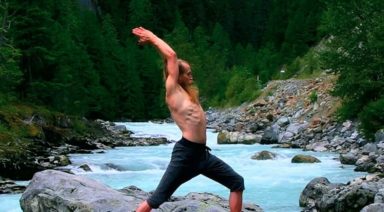

When we combine external rotation of the shoulder with upwards scapular abduction, this becomes a movement of integrity and beauty for the shoulder joint – retaining space while enhancing stability. Consider all the yoga postures and transitions where you can take advantage of this movement combination: sun salutation arm circles; downward facing dog; tree pose; crescent lunge/warrior 1; half moon; and other reaching side bends.

Play with these movements in the shoulder and shoulder girdle. Keep in mind that bone structure can be highly variable, therefore some people benefit more from these movement applications than others. Also examine with these movements how the rest of the body (and kinetic chain of other joints involved like the elbow and wrist) is affected. Rarely in yoga are movements tightly isolated in one joint region. As you find your way into postures, maintain ease and playfulness (versus rigidity) as this will greatly increase your capacity to explore these techniques towards spaciousness and integrity.

3 Exercises to Strengthen Your Hips and Balance Your Body

In yoga we often speak of tight hips, needing to open the hips, balancing the opening of our hips from side to side (etc), but there is more to a balanced body than open hips. We also need stability and support from our hips. This is important not only in yoga but also in day-to-day activities like simply walking. It is especially important if you are an athlete and need to perform on one leg.

A Look Inside the Hip Our hip musculature is made up of many muscles, large and small. For stability, we need the muscles of the side of the hip to be active and engaged. If you place your hands on the sides of your bony pelvis below your waist, you can imagine a tear-drop-shaped area below the ridge of your pelvis. The front part of the tear is the Tensor Fasciae Latae or TFL which connects with your IT band to join at the knee. At the back part of the teardrop are the Gluteus Medius and Minimus, which lie underneath your big Gluteus Maximus.

These muscles are what support and keep you steady in balance poses or when you transfer weight from one leg to the next as you walk or run. For many of us, these muscles are fast asleep, so we recruit our hip flexors at the front or our glutes and our hamstrings at the back to do a job they were not designed to do. Over time this can lead to low back pain and sacroiliac joint pain. Forcing our body to compensate will lead to problems over time. A look outside the hip Tree pose can be a simple test to see if we are accessing our side/lateral hip stabilizers.

Stand in front of the mirror and take a medium-size tree pose with your foot resting on the shin (even if you can go higher). Place your hands on your bony pelvis again and see if they are level from side to side. If not, press the shin into the foot and the foot back into the leg so that the standing hip drops to make the hips level. If this is too difficult to achieve, keep your foot off the ground but come out of tree pose so that your knee is facing forward, raised to hip level with the knee bent.

Try to level the hips again here by firmly rooting into the ground with the standing leg. My Three Favorite Lateral Hip Exercises Most of us can benefit from a little extra love and attention to the side of our hips. Try these exercises to wake up your hips and begin to stand taller on one leg

1. Kick the Ball Standing: Lift one foot off the ground. Keep your leg straight and send your heel forward, toes pointing out as if you were passing a soccer ball in slow motion. Reverse this motion by turning your toes in and sending your leg behind you. Flow forward and back, heel in and out, in a short arc. Don’t forget about your standing leg: root into the earth and don’t let the hip hitch out to the side. Repeat this motion ten times and then switch sides.

2. Clam Shell: Lie on your side with either your arm or a foam block supporting your head. Bend both hips to 90 degrees with knees bent, feet touching, stacked on top of each other. Slowly lift your top knee up towards the sky while keeping your feet together (as if you were a clamshell opening). Keep your hips stacked and avoid rotating with the pelvis. Lower, repeat times, and switch sides.

3. Bicycle: Lie on your side with both legs straight. Flex your feet, as if standing, and stack them on top of each other. Lift your top leg so that feet are hip-width apart. Keep this distance as you flow through this sequence: a) knee bent move forward to the hip at 90 degrees, b) straighten at the knee, c) float straight leg back to start. This should look like you are slowly pedaling a bike. Keep the hips stacked and stable. Strengthening our lateral hips will not only improve our yoga practice, but will also balance our body and prevent injury so that we continue to walk, vinyasa, and run for years to come.