Tamoanchan – The Journey to Paradise

Heaven, nirvana, Zion — whatever you want to call it, religions and cultures around the world differ in their beliefs about where we go after we die.

For the indigenous peoples of Mexico, they had a bit of a different view of the afterlife. Instead of automatically landing a place amongst the clouds or stars, a deceased person had to do some work to earn a spot in paradise in a place known as Tamoanchan, or the “place of the misty sky.”

What is Tamoanchan?

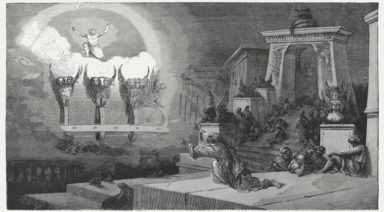

Tamoanchan is a mythical paradise that, depending on who you ask, is associated with Aztec or Mayan culture. Like many other cultures, these indigenous peoples believed after a person died, he or she would eventually end up in Tamoanchan. They also believed Tamoanchan was a home to the gods and the birthplace of mankind, time, and the calendar.

Tamoanchan is mentioned in the Tovar Codex, a work by Mexican Jesuit Jovan de Tovar. In the Codex, he describes Tamoanchan as “the Aztec equivalent of the Garden of Eden.”

However, there are some key differences between Tamoanchan and comparable concepts of the afterlife. Unlike heaven and similar places, Tamoanchan is not located in the sky — rather, it’s a place on Earth, situated on top of a mountain. This parallels the concept of Mount Belukha, being the gateway to the Buddhist paradise of Shambhala.

Secondly, the indigenous peoples did not believe one automatically went to Tamoanchan after death except under very rare circumstances. Instead, after dying, the deceased began a journey that would ultimately lead them to Tamoanchan.

The Journey to Tamoanchan

To reach Tamoanchan, the deceased had to first pass through a dark underworld called Xibalba, or “place of fright.” In Xibalba, they would encounter difficulties as the residents there would attempt to trick them into staying and not moving on to Tamoanchan.

According to legend, the Tree of Life sprouted from Xibalba and extended all the way up to Tamoanchan. After successfully passing through Xibalba, the deceased would then move up through a series of other worlds on the Tree of Life and eventually reach eternal paradise in Tamoanchan.

Under very rare circumstances, some individuals were exempt from the journey and could go directly to Tamoanchan after death. These circumstances included:

- Human sacrifice – Human sacrifice played a big role in Mayan culture. The Mayans had a cyclical view of life, believing people never truly died. Rather, they believed death was simply a part of life, and sacrifice was a surefire way to land a seat amongst the gods.

- Suicide – Suicide was also considered an honorable way to die in ancient Mesoamerican culture.

- Death in childbirth

- Death in combat

- Death on the ball court – The Mayan game Pok-a-tok was a sacred ritual that represented the struggle between life and death. The winning team had the privilege of being sacrificed to the gods, granting them direct access to paradise in Tamoanchan.

Tamoanchan: Fact or Fiction?

There are some who believe Tamoanchan isn’t merely a myth but an actual place. This draws back to the idea that Tamoanchan was located on Earth rather than in the heavens.

Researcher Alfredo López Austin claims Tamoanchan could have been located in several places, including Cuernavaca and near Iztactepetl and Popocatepetl. Other historians allege the mystical place was near the Gulf Coast.

Despite the many theories of Tamoanchan’s location, no one can be certain of its existence. There are many books out there about Mesoamerican mythology and history that can serve as resources, should you decide to conduct your own research on this fascinating topic.

Want more like this article?

Don’t miss Ancient Civilizations on Gaia to journey through humanity’s suppressed origins and examine the secret code left behind by our ancestors.

An Ancient Psychedelic Brew & Metal Found in an Elongated Skull

Did ancient Peruvian leaders use hallucinogens to keep their followers in line? And do an ancient elongated skull show evidence of an advanced metal surgical implant or is it just a hoax?

Archaeologists studying the Wari people in the southern Peruvian town of Quilcapampa have found hallucinogenic “vilca” seeds in a recent dig. Writing in the journal Antiquity, the researchers point out they found 16 vilca seeds in an ancient alcoholic drink called “Chicha de Molle,” in an area believed to be used for feasting.

The Wari people lived in this area from about 500 to 1,000 A.D. Their reverence for the psychotropic vilca seed has been found in images at other Wari sites, this is the first find of the actual seeds. What is particularly interesting to the archaeologists is the role of ancient hallucinogens and their influence on social interactions.

The vilca seeds would have come from tropical woodlands on the eastern side of the Andes, a complex trade network would have to be in place to even get them. And adding the vilca seeds with the alcoholic drink would increase the intensity of a psychedelic trip.

That trip would be seen as a journey to the spirit world, and Wari leaderships’ control over the substance led to control over their followers who wanted it. Researchers argue in their paper, “[T]he vilca-infused brew brought people together in a shared psychotropic experience while ensuring the privileged position of Wari leaders within the social hierarchy as the providers of the hallucinogen.”

Work continues at the dig site at Quilcapampa, and researchers plan to test where the ancient vilca seeds came from – so they can figure out the rest of the ancient trade routes.