The Yoga Pose You’re Doing Wrong (and How to Modify it Safely)

Take any yoga class and it’s almost guaranteed that you’ll do downward facing dog, or adho mukha svanasana, at least once. If you’re a fan of flow classes, the amount of times you’ll find yourself in down dog increases exponentially. For beginners, despite their teacher’s touting down dog as a pose of rest, it feels less like rest and more like a full body workout. This isn’t exactly untrue. When downward facing dog is executed properly the core is engaged and the entire back body is stretching, with the arms bearing some of the body’s weight, making down dog a pose that works the entire body from hands to heels. A correctly executed down dog also has many physical and mental benefits, including building bone density, increasing circulation, developing flexibility, calming the mind and counteracting fatigue. But when done wrong the benefits of the posture may be lost and put the yogi at risk for injury, especially if they’re hitting downward facing dog repeatedly.

Most of the students I see in class doing down dog incorrectly are making the same mistake. They slump forward into their shoulders, hunching their upper back and misplacing the majority of the weight from their trunk and hips into their shoulders and wrists. The shoulder, a ball and socket joint, is a shallow joint with a complex network of muscle and ligament attachments. This gives the joint a lot of flexibility but also increases the risk of injury, especially dislocation or wear and tear injuries involving the rotator cuff. Shoulder injuries can be extremely painful, and in some cases, can become chronic problems. Because of the complexity of the shoulder’s structure and a modern lifestyle that doesn’t always encourage strong muscle development in the area, shoulder injuries can be hard or impossible to repair, even with surgery. This makes properly practicing poses where the shoulder can be vulnerable, such as down dog, extremely important. Yoga is supposed to make us feel good inside and out, not leave us with chronic pain.

So how do you know if you are doing down dog correctly? First and foremost, listen to your body. If you are feeling discomfort or sensations that don’t resemble the description above, chances are something is off. Are the heels of your hands digging uncomfortably into the ground? Do your shoulders feel heavy and seem to sag toward your ears? Is there little to no feeling of stretch happening throughout your back or hamstrings? Does it feel as though your back is curving upward, like it does during cat pose? These may be signals that you need to make adjustments.

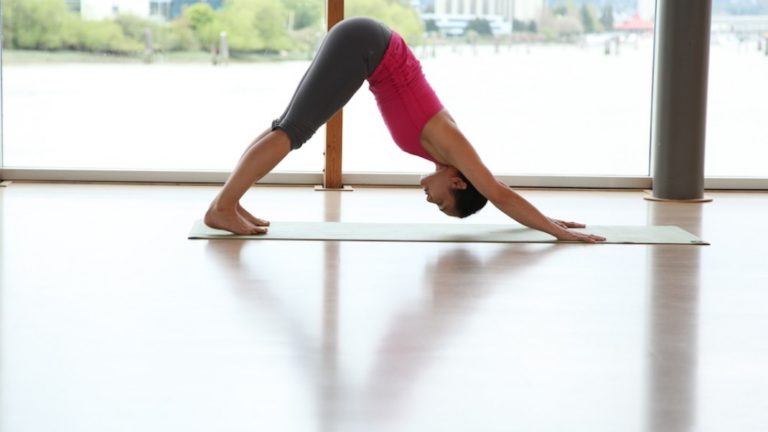

In a proper down dog the base of the pointer and pinky fingers and the heel of the hand should be pressed firmly into the mat. The arms should feel engaged, long, and be externally rotating, with the bony part of the elbows tracking backwards toward the body, rather than facing outwards. The shoulders should be pushing back from the ears with the shoulder blades pressing flat to the ribs. The back body should feel long and flat. The hips should continue this line, so that the entire top half of your body creates a long line from the base of the hands to the tailbone. The legs should feel a stretch through the hamstrings, with the knees straight, but not locked, and the heels pressing toward, or onto, the mat. The feeling should be of the thighs pressing back away from the arms. The lower half of the body is ideally a long line from hip to heel. The entire pose should look like two lines forming an inverted “V”.

Aren’t there exceptions to every rule? Isn’t a yoga practice about showing up and working to your level, rather than striving for the perfect posture all the time? Absolutely. But there is a difference between working on a posture where you are at, and working on a posture unsafely, even if you aren’t striving to put your body into a pose it isn’t ready for. As practitioners, part of being accountable for our practice is seeking guidance when something doesn’t feel right for our bodies. This goes beyond listening to descriptions or corrections given out in class. It means remembering that being pro-active can save us from unnecessary injury or chronic pain. If your down dog doesn’t seem quite right, an experienced teacher can provide you with the guidance to modify it to suit your body and practice while allowing you to safely reap the benefits of the pose.

Yoga Poses to Ease Digestive Discomfort

If you’re one of the many American who suffers from occasional digestive discomfort, yoga offers a natural way to get relief. Just as you would adapt your diet to address your needs, try including some of these poses into your regular practice.

Cat-Cow – Marjaryasana-Bitilasana

- Improves posture and balance

- Strengthens and stretches the spine and neck

- Stretches the hips, abdomen and bac

- Increases coordination

- Massages and stimulates organs in the belly, like the kidneys and adrenal glands.

- Relieves stress and calms the mind

Downward-Facing Dog – Adho Mukha Svanasana

- Calms the brain and helps relieve stress

- Stretches the shoulders, hamstrings, calves, arches, and hands

- Strengthens the arms and legs

- Relieves headache, insomnia, back pain, and fatigue

- Therapeutic for high blood pressure

- Helps prevent osteoporosis

Extended Puppy Pose – Uttana Shishosana

- Releases tension in you upper arms, shoulders, and neck

- Expands the whole front of your chest

- Stretches out your abdominal muscles

- Gently stimulates your back muscles in preparation for further backbends

- Opens up your hips and stretches your hamstrings

Bridge Pose – Setu Bandha Saravangasana

- Streches your chest, neck, spine, and hips

- Strengthens your back, buttocks, and hamstring muscles

- Calms your brain and central nervous system

- Alleviates stress and mild depression

- Massages abdominal organs and improves digestion/li>

- Relieves the symptoms of menopause

- Reduces anxiety, backaches, headaches, and insomnia

Wind-Relieving Pose – Ardha Pawanmuktasana

- Stretches the neck and back

- Pressure on the abdomen releases any trapped gases in the large intestine

- Blood circulation is increased to all the internal organs

- Relieves constipation

- Strengthens the back and abdominal muscles

- Massages the intestines and other organs in the abdomen

- Eases tension in the lower back